California’s Geologic Building Blocks, and the Accretionary Wedge

I have been looking forward to researching and writing about accretionary wedge formation and theory for a while – it’s an exciting geologic phenomenon of tectonics which underlies much of western California. But I soon realized that this one element of our subduction complex geomorphology could not be analyzed alone. To make sense of it all, I had to examine accretionary wedge evolution in the context of the broader concept of California’s accreted “terranes” and the monumental westward formation of our coast and state as a whole. It is just one piece in the jumbled and morphing puzzle of this living landscape. So here is my run-down of the moving pieces of California’s basic geologic building blocks and events, and how the western Cordilleran accretionary wedge fits in..

Building Blocks

Firsts

Representing what could be an ancient rift valley at the splitting apart of continents over 1.2 billion years ago, the oldest rocks in California date to the Precambrian, before life existed on earth. These rare ancestral plutonic and metamorphic outcrops can be found in faint scatterings across far southeastern California’s Mojave Desert, and within the San Bernardino and San Gabriel Mountains.

Paleozoic Metamorphics

The very basic geologic building blocks of California start with Paleozoic metamorphic rocks: remnants from a vanished passive continental margin along a tropical coast where the Basin and Range now lays in eastern California. Known as “roof pendants” in the high Sierra, and observed as metamorphic basement rocks in the foothills and within the Salinian Block, these ancient continental remnants are found in far flung patches from the ancient shore of eastern California to our present coastal front.

Conveyed and Accreted Terranes

For millions of years to follow throughout the Mesozoic, as the North American Cordillera was steadily constructed, pieces of ocean crust and exotic terranes were accreted on to this western margin, conveyed in on one or more eastward moving and subducting tectonic plates. At least five parallel belts of metamorphic terranes have been identified as smooshed together in the vicinity of today’s northern Sierra Nevada foothills.

Ancestral Subduction Volcanics

From the convergence of the oceanic Farallon Plate into and under the North American continental plate, millions of years of volcanic activity ensued, and plutonic bodies formed the massive granitic Sierra-Nevada Batholith. With the ceasing of subduction these ancient volcanoes snuffed-out and were eroded away. More recent thrust faults have exhumed portions of the batholith and erected the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

Remnant Ocean Crust and Overlying Sediments

West of this rising volcanic arc of the ancestral Sierras, a submarine forearc basin was formed. A weighty plain of fossilized oceanic crust, and overlying marine deposits from this ancient ocean basin still holds its tub-like form as the Central Valley. And I would argue this is the most striking geomorphic feature of western North America when viewed from satellite imagery.

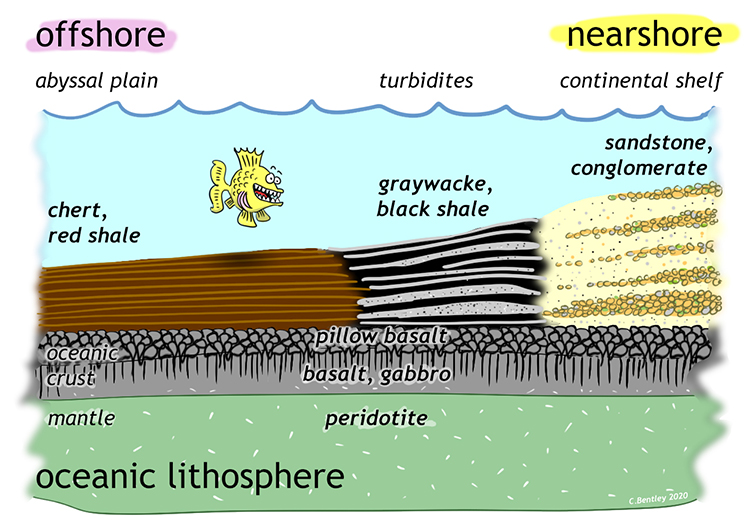

Accretionary Wedge

At the western border of the forearc basin, an accretionary wedge, or prism, was formed as masses of ocean crust material scraped off the subducting Farallon Plate on to the edge of the continental margin. At this Cordilleran subduction zone igneous basalts, deepwater sedimentary deposits of Chert, and shallower sedimentary sandstones and mudstones (mostly Greywacke) conveyed in and accumulated to form the geologic elements of the wedge. Unique to this geologic environment are metamorphic rocks, such as Serpentinite and Blueschist, which are formed within the subduction zone.

California’s state rock, the metamorphic Serpentinite, forms when ultramafic Peridotite from within the earth’s mantle, gets squeezed up through the oceanic crust and comes in contact with sea water, which changes its chemistry and composition. Blueschist is a rare example of high grade metamorphism, which only occurs under high pressure and high heat deep in a subduction trench. Outcrops of Blueschist are beautiful and rare. Highly studied outcrops are found atop Ring Mountain Preserve on the Tiburon Peninsula.

All of this subduction trench and accretionary wedge material solidified to form the famous Franciscan Complex, or Franciscan Assemblage. The Franciscan Assemblage is presented in geologically unique terrain packages – units which “arrived” or developed during distinct time periods. The Franciscan Melange is a signature geomorphic feature which shapes much of California’s pastoral Coast Range landscape.

Accreted Terranes of the Klamaths

Artifacts of the accretionary wedge and the geologic body of the Franciscan Complex extends from the Transverse Ranges in the south to Southern Oregon in the north, narrowly skirting the coast in a five mile-wide swath at the western border of the Klamath Range. For millions of years the Klamath geomorphic province was formed by a series of at least five eastward accreting terranes (younger in age in a westward succession) comprised of oceanic plate material, sedimentary plateaus, and volcanic arcs. This succession of terrane arrival and continent building parallels that of the accretion events and terrane arrivals of the northern Sierra Nevada.

As the Cenozoic era unfolded subduction of the Farallon Plate ended with the convergence of the mid ocean ridge and spreading center with the North Amercian Plate, and the slow transition to a broad northwesterly-grinding Transform boundary fault system took over.

Cenozoic Volcanic Belt

Younger Cenozoic volcanic activity has followed (dragged behind) the northwestward migration of the Mendocino Triple Junction which sits at the leading edge of the expanding San Andreas transform fault system. Remnants of this Cenozoic volcanic trail can be found from Neenach Mountain to the south in the western corner of the Mojave Desert (half of this volcano was split off and carried almost 200 miles northwest by the San Andreas Fault to form the Pinnacles in Monterey County); to the Morros of San Luis Obispo County; to volcanics in the Diablo Range, the Berkeley Hills, the Sonoma Volcanic Field; and finally to the Clear Lake Volcanics in the north, which are as young as 10,000 years old. Glimpses of this volcanic activity can be seen (and experienced) today at The Geysers geothermal belt, and in the hot springs of Sonoma, Napa, and Lake County.

The Salinian Block

A major Cenozoic feature of California’s evolving structure is the ongoing transport of the Salinian Block: a mighty granitic tail of the Sierra-Nevada Batholith, ripped off from its southern roots by the new San Andreas transform fault system and dragged northwestward. Swaths of the Salinian Block are mainly found offshore, and in mountainous outcrops along our coastline including the Sierra de Salinas, Point Lobos, Montara Mountain, the Farallon Islands, The Point Reyes Peninsula, and Bodega Head.

Cenozoic Sedimentary Basin Deposits

Topping off the basic geologic building blocks of California, younger Cenozoic sedimentary basin deposits abound across the state: formed at the waxing and waning of ice age shallow marine basins as sea levels and precipitation rates fluctuated.

Continuing Subduction Volcanics

And of course oceanic to continental plate subduction volcanic activity continues to occur to this day in California’s Cascade Mountains and the Modoc Plateau geomorphic provinces.

Accretionary Wedge Today

The Coast Range geomorphic province is an assemblage of many smaller northwest trending ranges and valleys, following the broad tectonic line of the transform plate boundary. The Coast Range in California is constructed primarily of the Franciscan Complex, but also derives some structure from the Salinian Block, the Great Valley Sequence, and Cenozoic sedimentary deposits. When observing the Coast Range, or ranges, one is viewing the mark of the ancient Cordilleran subduction zone, now uplifted by ongoing subduction and transform tectonic activity. The Franciscan Formation within the Coast Range embodies what remains of the accretionary wedge and of the Farallon Plate itself.

Resources and Further Reading:

Alt, David and Donald Hyndman. 2017. Roadside Geology of Northern and Central California. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Company.

Atwater, Tanya M. 1970. “Implications of plate tectonics for the Cenozoic evolution of western North America.” Geological Society of America Bulletin 81: 3513-3536. DOI: 10.1130/0016-7606(1970)81[3513:IOPTFT]2.0.CO;2

Blakey, Ronald, and Wayne Ranney. 2018. Ancient Landscapes of Western North America. Gewerbestrasse: Springer.

Harden, Deborah. 2004. California Geology. Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Sloan, Doris. 2006. Geology of the San Francisco Bay Region. Berkeley: University of California Press.

North American Cordillera – USGS

Accreted Terranes of Cordillera – NPS

California’s Coast Ranges: A Mesozoic Accretionary Wedge Complex – Open Geology online textbook

Discover more from Cal Geographic

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.