The Chaparral Mosaic in California

If one ecosystem typifies California, it is chaparral. Enduring, somber, vast – often mythologized – chaparral is emblematic of our wild west. The quintessence of a rugged and calamitous geography; a resilient and seemingly impenetrable mosaic of diversity and endemism; chaparral is California.

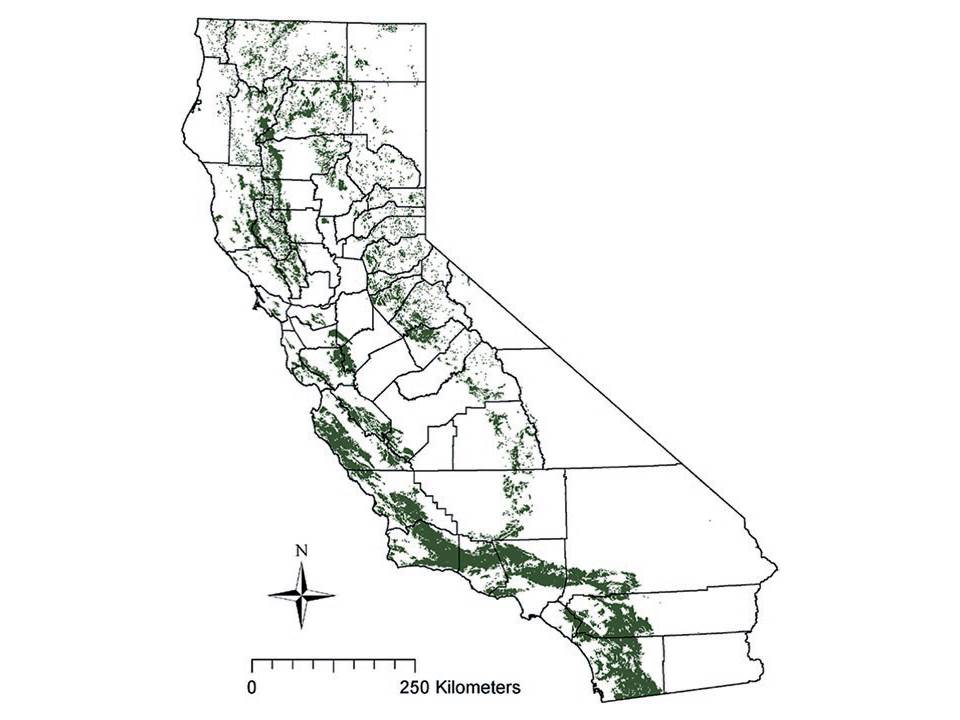

Yes, it’s that important. The chaparral community mosaic covers the most area of any botanical assemblage or habitat type in California. It dominates the inland foothills and mid-level mountain slopes of the Peninsular, Transverse, and Coast Ranges – especially in Southern California – as well as the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, the Klamaths, and the Cascade Mountains. Rare chaparral communities are also found in sparse patches at sea level and in the lower coastal foothills up to Mendocino County.

Chaparral predominantly occurs in Southern California and inland between 500-4500 feet of elevation, but Montane chaparral communities can be found upwards of 7000 feet in elevation. Chaparral-like communities radiate south into north and central Mexico; eastward throughout higher elevations of the Basin and Range and Arizona; and scattered up into dry central and eastern Oregon and Washington.

Structurally, chaparral is characterized by dense, almost impenetrable stands of large evergreen and sclerophyllous woody shrubs, usually occurring on xeric and hilly landscapes. Woody dominants of the chaparral are adapted to tolerate summer drought and fire regimes (with moderate to infrequent wildfire intervals, approximately one to three times per century – some communities cannot withstand wildfire more than every 150 + years). Emblematic of a Mediterranean Climate, chaparral communities depend on summer drought and cool winter rains to varying degrees.

The three major environmental drivers of chaparral community evolution and diversity are soil characteristics, wildfire regime intervals, and the Mediterranean Climate.Within these three categories, unique chaparral community composition develops based on water availability, soil nutrient availability, and other factors such as elevation, slope, and aspect.

Mixed Chaparral, R. Forest

Most chaparral communities are found on nutrient poor, shallow, and coarse grained to rocky soils; but some lower elevation and coastal chaparral communities depend on thicker marine soils. While most woody chaparral shrub species can tolerate drought within the parameters of annual and decadal Mediterranean climatic swings, chaparral communities and individual species become stressed in prolonged and extreme drought, and can suffer physiological loss. The same goes for chaparral and wildfire.

A common misconception about chaparral is that it is prone to and can tolerate frequent wildfire. This is far from the truth. While most chaparral communities have evolved with wildfire, and to tolerate specific and infrequent crown fire regimes, they cannot tolerate frequent human caused burns. If burned too frequently chaparral communities do not have enough time to reproduce, succumb, and transition often to weedy annual grasslands. Different chaparral communities are adapted to different wildfire intervals, and some, such as the mesic Maritime Chaparral communities, rely on summer precipitation from marine fog, and very infrequent low intensity wildfire.

Due to such an extensive latitudinal, longitudinal, and elevational range, which results in diverse climatic and soil influences, the species composition between chaparral communities in California is notably diverse and distinct from each other. This has led to an effort to categorize and classify the major chaparral communities. Over the years chaparral communities have been named based on dominant woody species (Chamise chaparral, Manzanita chaparral, Ceonothus chaparral, etc); soil type (Serpentine and Dune chaparral); and geography (Channel Islands, Maritime, and Montane chaparral communities).

Later in the 20th century, the national hierarchical vegetation classification system was applied to California’s floristic communities, classifying 9 undifferentiated chaparral scrub types, with over 60 chaparral alliances within these types. It is felt that classification of community types and alliances is somewhat arbitrary and based on preference, since species composition overlaps in much more complex patterns between communities, creating a landscape mosaic which is difficult to capture categorically. However, there is use to categorizing or classifying floristic communities and habitats in order to aid inventory and conservation efforts.

Amongst all this community complexity and diversity (including the evolution of over 100 woody chaparral shrub species!) there is one unifying presence, Chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum) : a shrub found throughout the entire range of chaparral, and in all communities but a very small few. Other dominant and emblematic woody shrubs of the California chaparral communities include manzanitas (Arctostaphylos spp,) and Ceonothus spp.

The development and diversity of chaparral communities is facilitated by three primary reproductive strategies of chaparral plant species in response to evolving with wildfire: obligate resprouting, obligate seeding, and facultative seeding. Obligate respouters survive wildfire when burned, and persist by resprouting from a mature individual’s burned stems and root crowns. Facultative seeder species may or may not perish when burned as adults, and produce long lived seed banks with seeds that are dormant at maturity, triggered to sprout only when burned. Obligate seeder plant species die when burned as adults, and rely solely on the triggering of fire-tolerant seed banks to resprout and reestablish their populations. The two seeder groups of chaparral plants, produce either long lived/long dormant “persistent” seed banks, or “transient” seed banks which survive dormancy for shorter periods/rely on shorter interval wildfire regimes.

Species diversity within a chaparral community is highest directly following a wildfire when multiple species reproduce at once. A panoply of woody and herbaceous species (including annuals) vigorously resprout and emerge from seed banks directly after the fire interval occurs, and over time this diversity declines as the dominant woody species grow to take up the majority of resources and space within the community.

This interesting fact of the cyclic nature of chaparral communities does not mean that a community begins to senesce or continue to decline in diversity after reaching a peak of maturity. In fact, mature and “old growth” chaparral communities continue to maintain a high level of ecosystem support and productivity, and rely on very long intervals between the regenerating wildfires to flourish as an ecosystem. While continuing to sequester carbon, mature and old growth chaparral communities support and are supported by a web of ecological relations with invertebrates, birds, mammals, lichen and fungal/ mycorrhizal networks – many endemic to these chaparral communities.

These life history strategies within chaparral communities, coupled with specific soil, water, and climate factors, have led to high endemism locally within chaparral communities, particularly for woody shrubs such as manzanitas.

One of the most unique and endangered chaparral communities is Maritime chaparral. It is found along the California coast in verdant patches at distinct locations such as amongst the crumbling ruddy sandstone terraces of Torrey Pines State Preserve; the Los Osos Elfin Forest Preserve rimming Morro Bay; the back dunes of Monterey Bay at Fort Ord; draping the tentacled granite ridges of Montara Mountain looming over the San Mateo coast; and in remote sky-island patches amongst a sea of evergreen forest atop Mount Tamalpais’ inaccessible and majestic slopes in west Marin county, plunging seaward down into the San Andreas Fault.

Several important environmental factors come together to create this fragile ecosystem. Like other chaparral communities Maritime chaparral occurs in coarse grained/gravely and thin soils (in this case featuring heterogeneous azonal soils, and that is where the similarities end. Foremost, Maritime chaparral is exposed to higher summer moisture availability than other chaparral types, as it lies within the influence of the summer marine fog belt, and enjoys increased winter precipitation from the coastal uplands. The major evolutionary driver of greater water availability has encouraged very long wildfire intervals in the Maritime chaparral, and in turn has selected for obligate seeder species.

Maritime chaparral is unique also for its paucity of Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), and instead is dominated by myriad Arctostaphylos species (manzanitas). There is very high endemism of Arctostaphylos species in California, and this phenomenon is magnified in the coastal zone. Relatively moist conditions, long fire intervals, isolation of habitat patches, and other baseline environmental factors such as soil characteristics and overall Mediterranean climatic influence, have led to rapid hybridization of manzanita species in the Maritime chaparral.

Endemic Arctostaphylos montaraensis (Montara Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos sp. in Maritime Chaparral Mount Tamalpais, R. Forest

Wildfire selects for the stronger hybrid species within the isolated habitat patches, eventually leading to the evolution of new species, or neoendemics. These hospitable mesic chaparral patches in the maritime zone have also become refuges for paleoendimcs –archaic manzanita and other woody species. Over half of California’s manzanita species (approximately 46 out of 96 taxa) are endemics of the coastal zone, and of the Maritime chaparral.

Evergreen shrubs of arid environments are seen in the fossil record as far back as the Cretaceous and early Tertiary periods, but based on analysis of the botanical fossil record, it is believed that chaparral species and habitats developed and expanded as the Mediterranean climate developed in the early to mid-Miocene epoch. As climatic drying has increased in California since the Pleistocene epoch, the range of chaparral has expanded northward.

“In the mountains of San Gabriel, overlooking the lowland vines and fruit groves, Mother Nature is most ruggedly, thornily savage. Not even in the Sierra have I ever made the acquaintance of mountains more rigidly inaccessible. The slopes are exceptionally steep and insecure to the foot of the explorer, however great his strength or skill may be, but thorny chaparral constitutes their chief defense. With the exception of little park and garden spots not visible in comprehensive views, the entire surface is covered with it, from the highest peaks to the plain. It swoops into every hollow and swells over every ridge, gracefully complying with the varied topography, in shaggy, ungovernable exuberance, fairly dwarfing the utmost efforts of human culture out of sight and mind.” John Muir, 1875

Resources and Further Reading:

California Chaparral Institute

Barbour, Michael, T. Keeler-Wolf, and A Schoenherr. 2007. Terrestrial Vegetation of California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mooney, Harold and Erika Zavaleta. 2016. Ecosystems of California. Oakland: University of California Press.

Rundel, Philip W., 2018. California Chaparral and Its Global Significance. Los Angeles: Springer DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-68303-4_1

Vasey, Michael C., Michael E. Loik, V. Thomas Parker. 2012. “Influence of summer marine fog and low cloud stratus on water relations of evergreen woody shrubs in the chaparral of central California.” Oecologia 170: 325-337. DOI 10.1007/s00442-012-2321-0

Vasey, Michael C., V. Thomas Parker. 2014. “Drivers of diversity in evergreen woody plant lineages experiencing canopy fire regimes in mediterranean type climate regions.” Plant Ecology and Evolution: 179-201

Vasey, Micahel C., V. Thomas Parker, et al. 2014. “Maritime climate influence on chaparral composition and diversity in the coast range of central California.” Ecology and Evolution 4: 3662-3674. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1211

Vasey, Michael C., V. Thomas Parker. 2016. “Two new subspecies of arctostaphylos from California and implications for understanding diversification in this genus.” Madrono 63 (3): 283–291

Discover more from Cal Geographic

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.