The San Andreas Fault System, Bay Area Fault Complex, and the Mount Tamalpais Blind Thrust

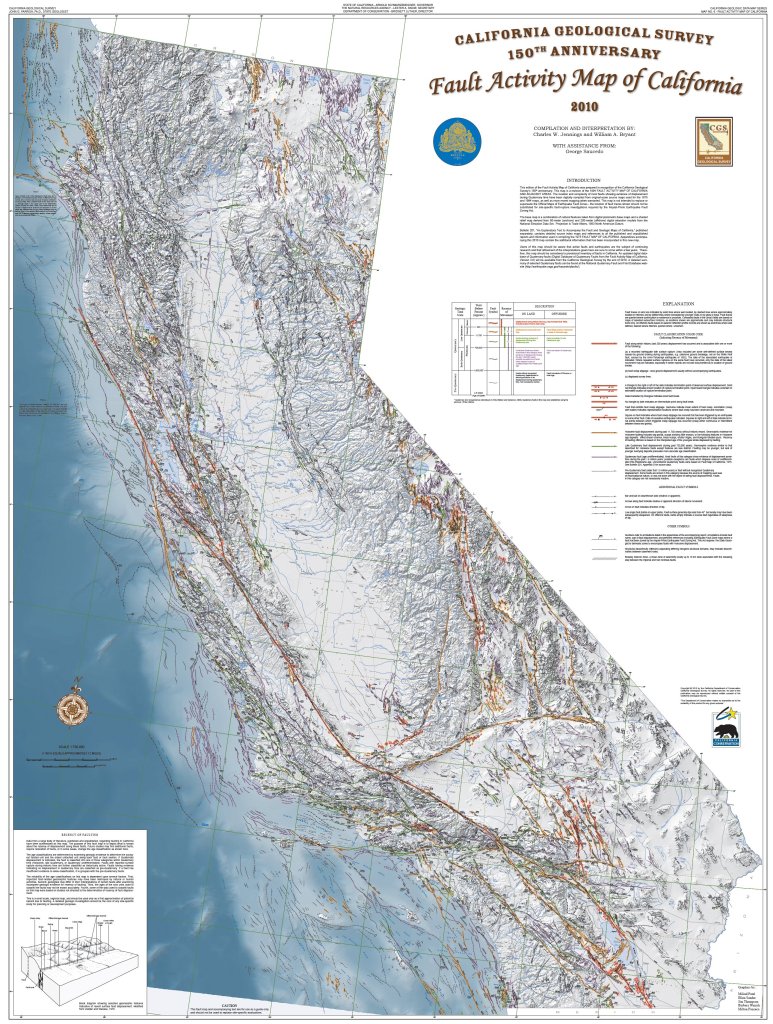

The San Andreas Fault is not only in constant motion it is also constantly evolving, expanding, and adjusting its course. With monumental reverberations of give and take, the greater San Andreas Fault system produces an ever-shifting network of compressional and extensional pressures, which in turn produce a vast network of compressional and extensional faults.

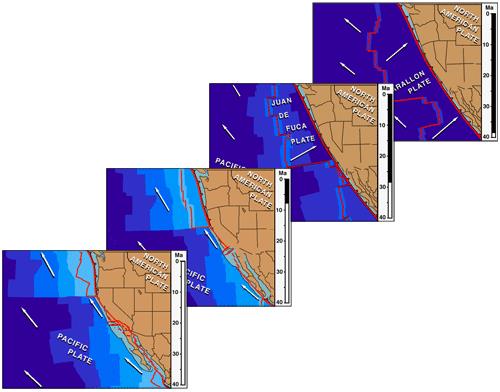

The San Andreas transform fault system came into existence between 20-30 million years-ago when the majority of the Farallon Plate subducted beneath the western edge of the North American Plate, ending with the subduction of the spreading center at its back edge and dragging behind it the leading edge of the mighty Pacific Plate. Although the Pacific Plate was being dragged eastward on its collision course with North America, the plate itself was rotating toward the west-northwest as it was being produced by new oceanic crust emerging from the oceanic spreading center. Thus, the northwesterly kinetic forces and transform movement at the edge of the Pacific plate took hold of the western boundary of North America, to form the San Andreas Fault (SAF) system.

As the SAF strengthened and expanded in a northwesterly direction over the past millions of years, forming the geomorphology of the California coast we see today, it has not behaved in a singularly smooth shear-like transform trajectory, but instead compresses and expands along its course, skipping and grinding in new directions. When outside forces such as the expansion of the Basin and Range, constraints along or formations of large opposing faults (such as the Garlock Fault), and the rotation or extension of adjacent landmasses due to subducting or enlarging spreading centers, the San Andreas Fault can jump course, creating small or massive bends along its rift zone. These forces and disruptions send tectonic shock waves throughout the San Andreas system, shift whole mountain ranges, open peninsulas to let in or block out the sea, and set in motion a fractured landscape of multitudes of semi-parallel tectonic faults, which take up and release these kinetic pressures across the state and out to sea.

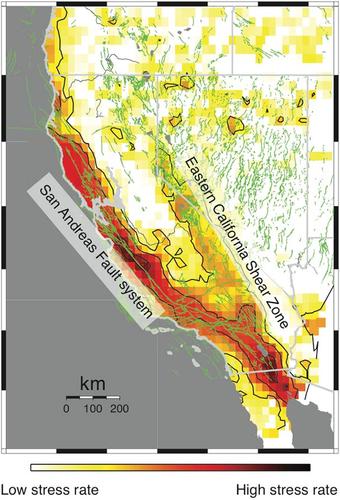

The San Andreas Fault (SAF) system (or shear zone, or fault complex) is found from across the state, from east of the Sierras in western Nevada, to several miles off the western shore of California. Young faults associated with the SAF system continue to develop, expand, and become apparent to humans. A 600-700 mile long belt of discontinuous strike-slip and “normal” (extensional) tectonic faults makes up the Walker Lane Belt/Eastern California Shear Zone a major force of movement and geomorphologic development within the SAF system – and believed by many geo scientists to signify the natal stages of western North America’s next transform fault system: eventually replacing the San Andreas Fault and creating a new west coast.

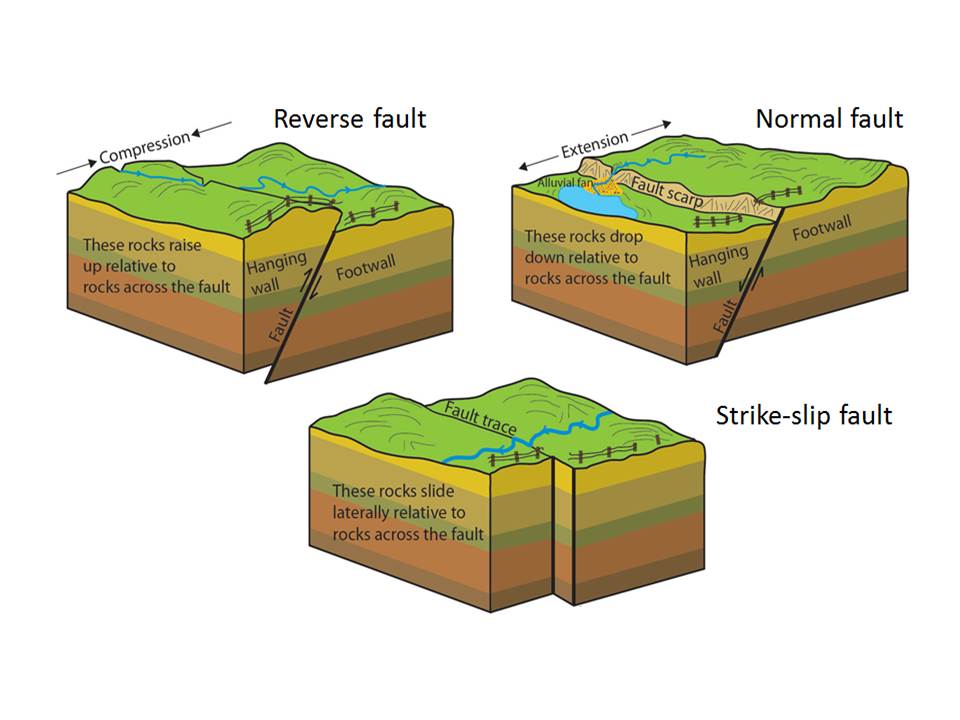

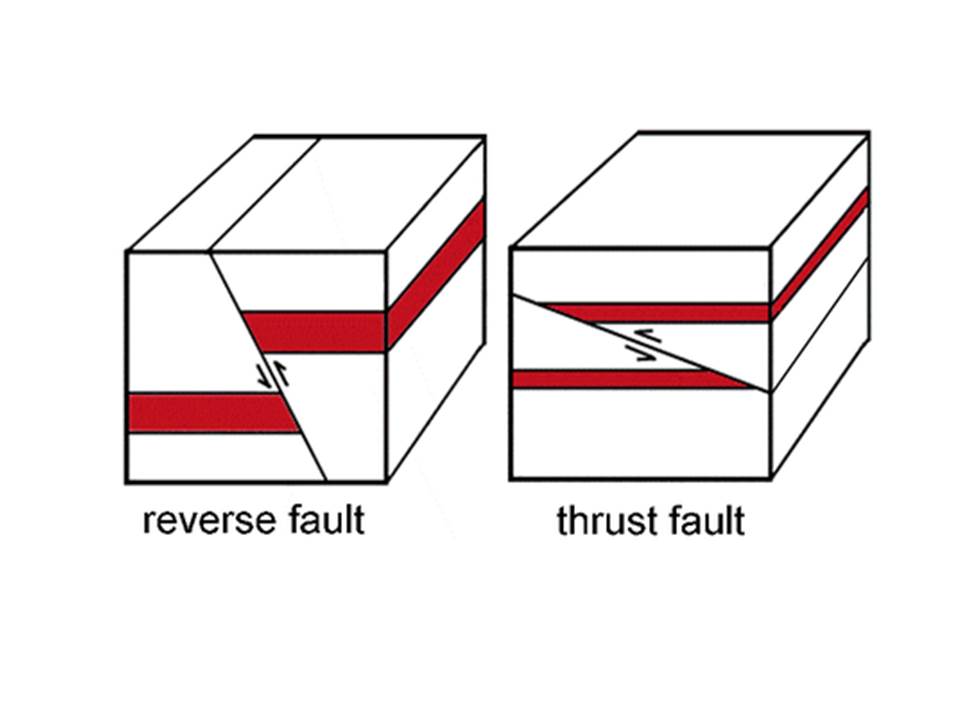

When identifiying tectonic forces of compression within a transform/strike-slip fault system or shear zone, the appropriate identifier is tranpression or transpressional forces. And when addressing extensional or pull-apart forces within a transform system, transtension or transtensional forces is the correct term. Transpressional forces account for the majority of land formation and deformation within the western region of the SAF system. Transpression occurs within the shear zone of a fault, and where the land is compressed between two or more transform faults. Transpressional force is expressed in reverse and thrust faulting, and produces uplifted landforms such as large and small pressure ridges.

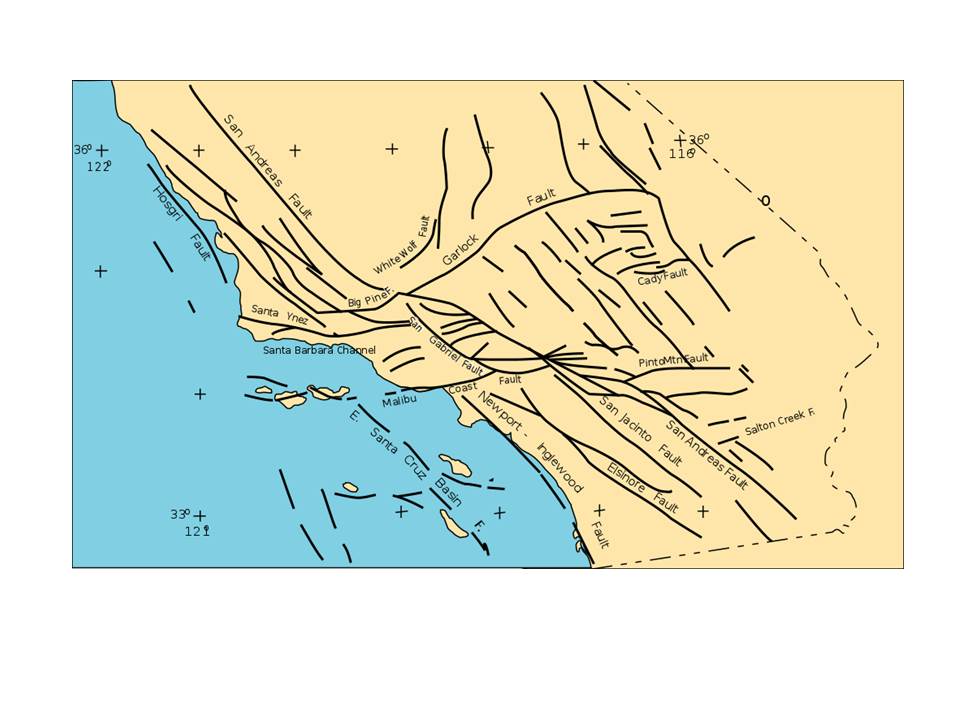

Along with the dominant strike-slip motion along the SAF zone, the Pacific and North American plates are also slightly colliding and compressing into each other, which generates transpressional forces that are building the Transverse, Peninsular and Coast Ranges of western California. When the Pacific spreading center trailing behind the Farallon Plate was finally pulled into the subduction zone and the rapid directional shift developed along the continental margin, a chain of massive transpressional geomorphic events took place including the compression and 90 degree westerly rotation of the Transverse Range.

Transtension also occurs in the western region of the SAF system where smaller stretches of the land on either side of transverse faults are moving away from each other, creating pull-apart basins. In the eastern region of the SAF shear zone east of the Sierras and in western Nevada, transtension is the dominant tectonic force, and it is believed to contribute to the ongoing extension of the western Basin and Range geomorphic province. The Basin and Range geomorphic structure is a massive and broad rift valley stretching and subsiding as the SAF system tugs at it from the west, and powerful “normal” faults at the Wasatch Front and along the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada create opposing extensional forces resulting in the dramatic Horst and Graben landscape of Nevada and beyond. Major transtensional forces of the SAF system also contributed to the rotation and opening of the arm of the Baja Peninsula and creation of the Gulf of California.

Today the San Andreas Fault system can be analyzed in three distinct sections: the southern, central and northern San Andreas Fault. In the southern region the SAF emerges from the spreading center of the Gulf of California and encompasses a complex fracture zone of very active lateral faulting, coupled with the rifting and tectonics of a divergent plate boundary through the Salton Trough. North of this at 33-35° latitude, the SAF takes on abrupt westerly turn, known as the Big Bend. The Big Bend in the SAF is where it meets the east-west trending transform Garlock Fault. Transpressional forces at the area of the Big Bend create the east-west trending Transverse Range.

The central region of the San Andreas Fault is much more linear, quiet, and less fractured than the complex southern and northern regions. Here the fault follows a more streamlined trajectory, and much of the energy and movement on the fault is expressed as gentle and mostly undetectable fault “creep”.

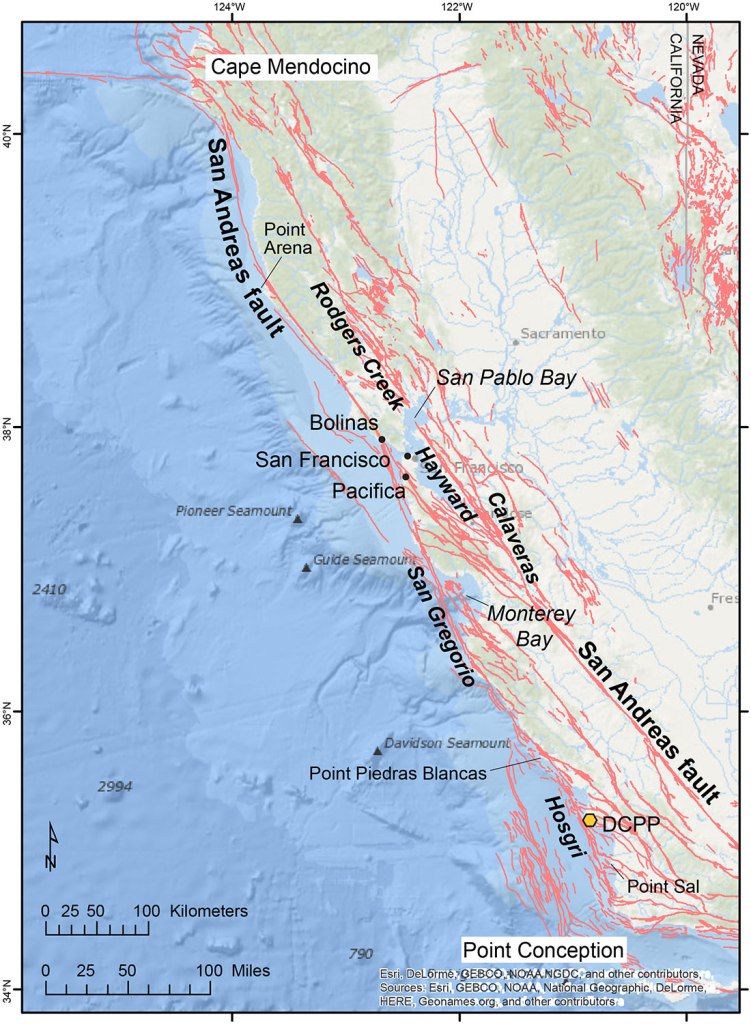

In the northern region the SAF system again fragments into a broad fractured field of semi-parallel muscular transform faults, flanking the SAF to the east and west and offshore. A slight bend in the SAF in the Santa Cruz Mountains may account for the tectonic complexity of the northern region. There are hundreds, if not thousands of small and undiscovered faults associated with the SAF in the Bay Area. Some of the transform biggies here include the Golden Gate, the San Gregorio, the Hayward, the Calaveras, the Rodgers Creek, and the Maacama faults.

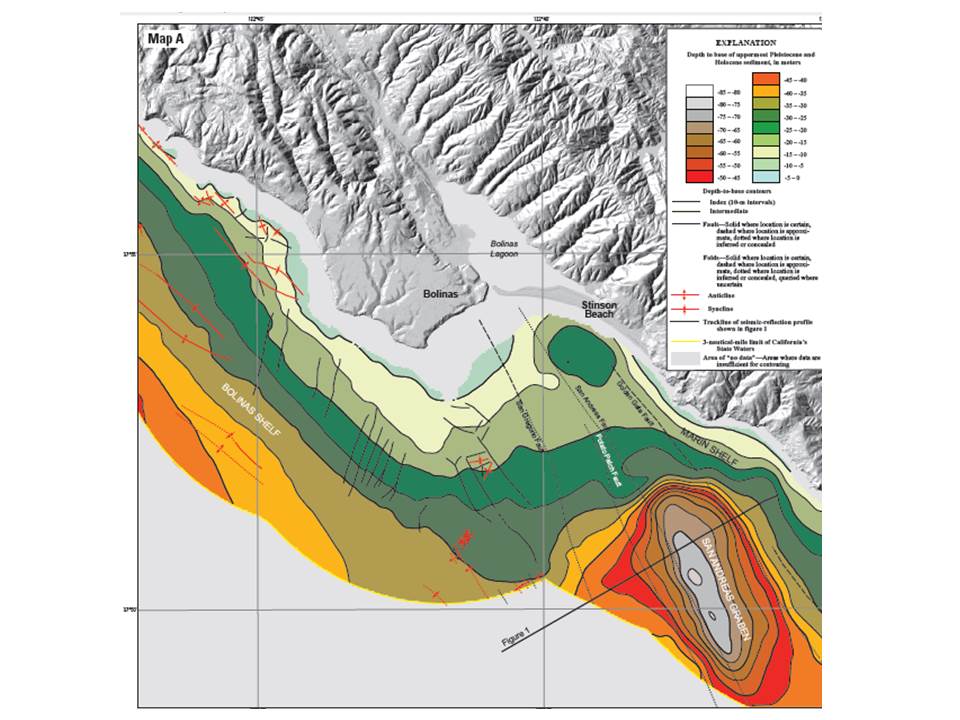

Within this northern transform system, transpression between faults prevails and creates a landscape of compressional structures, as well as numerous reverse and thrust faults. Smaller structures of transtension within the northern region, such as pull-apart basins and offshore grabens, also occurs, and are evidence of subsidence between transform faults, as well as possible normal faulting.

Just offshore and adjacent to the west Marin County coast, a prominent marine graben lies snuggly between submerged arms of the Golden Gate and San Andreas Faults. This submerged pull apart basin is deeper than the submarine crevasse beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, and indicates major transtensional forces and possible normal faulting at play along this famous stretch of the San Andreas Fault near the epicenter of the 1906 earthquake.

Close by the San Andreas Graben and a bit further offshore to the west, a zone of contraction has been found to be causing rapid uplift of the southern Point Reyes Peninsula. Here, a series of transpressional reverse faults have been discovered bridging two offshore segments of the San Gregorio fault, and are believed to be the source of the magnitude 5.0 thrust earthquake which occurred beneath the town of Bolinas at the southern tip of the peninsula in 1999: The first earthquake of its kind to make itself known in modern times in the area, with dramatic reverse fault behavior and vertical motion – direct evidence of ongoing uplift in the region.

Thrust faults caused by transpression in the northern SAF region have given rise to sentinel landforms across the San Francisco Bay Area, including the ongoing uplift and transport of Mount Diablo. To the west of Mount Diablo and along the coast, Mount Tamalpais rises from the north edge of the Golden Gate, dominating Marin County’s southwestern landscape. Geologists have long puzzled over the origins of Mount Tam, with no further explanation for its hefty 2,640 foot elevational presence than its probable transpressional ascension generated by an undiscovered “blind” thrust fault.

Blind thrust faults are completely subterranean, with no surface expressions (other than rising pressure ridges), and are next to impossible to identify until an earthquake occurs on such a tectonic zone. No earthquakes have been recorded emanating from a blind thrust fault under Mount Tam, and there are no historic elevation data of the ridge to analyze possible uplift rates.

But Tamalpais displays other tell-tale indicators of a blind thrust landform, including a steeply sloping ridge line thrust up at a sharper angle than the surrounding gentler slopes. The Bolinas Ridge on the southwestern flank of Mount Tam rises sharply from the Pacific Ocean and the Bolinas Lagoon. Its hillsides and canyon walls climb vertically in places, retreating into deep, dark ravines concealing forested plunging watercourses.

In order to test or identify possible uplift of Mount Tamalpais, recent geomorphic field studies have been conducted on the Bolinas Ridge to measure watershed hillslope gradient, channel gradient and profiles, erosion rates, and transient channel bedrock incision rates. The measures of incision rates have shown that steeply thrusting uplift is occurring on the southern flank of Mount Tamalpais, and stream erosion rates on these steep slopes is most likely outpaced by this uplift. It is estimated that the Bolinas Ridge is rising at a rate of .5-1.0 mm a year, and may have a slip rate of 3-4mm a year, which could produce earthquakes up to 6.5 in magnitude every few hundred years or so.

Resources and further reading:

Atwater, Tanya M. 1970. “Implications of plate tectonics for the Cenozoic evolution of western North America.” Geological Society of America Bulletin 81: 3513-3536. DOI: 10.1130/0016-7606(1970)81[3513:IOPTFT]2.0.CO;2

Aydin, Atilla, and Benjamin M. Page. 1984. “Diverse Pliocene-Quaternary tectonics in a transform environment, San Francisco Bay region, California.” Geological Society of America Bulletin 95 (11): 1303-1317. doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606

Grove, Karen, et al. 2010. “Accelerating and spatially-varying crustal uplift and its geomorphic expression, San Andreas Fault zone north of San Francisco, California.” Tectonophysics 495: 256-268. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2010.09.034

Harden, Deborah. 2004. California Geology. Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Johnson, Samuel Y., et al. 2015. “Local (Offshore of Bolinas Map Area) and Regional (Offshore from Bolinas to Pescadero) Shallow-Subsurface Geology and Structure, California.” USGS Map

Kirby, Eric, Courtney Johnson, et al. 2007. “Transient channel incision along Bolinas Ridge, California: evidence for differential rock uplift adjacent to the San Andreas fault.” Journal of Geophysical Research 112. doi:10.1029/2006JF000559.

Liu, M., et al. 2010. “Inception of the eastern California shear zone and evolution of the Pacific‐North American plate boundary: from kinematics to geodynamics.” Journal of Geophysical Research 115. doi:10.1029/2009JB007055.

Parsons, Tom, Jill McCarthy, et al. 2002. “A review of faults and crustal structure in the San Francisco Bay Area as revealed by seismic studies: 1991–1997.” Geology. 119-145.

Ryan, H.F., et al. 2008. “Vertical tectonic deformation associated with the San Andreas fault zone offshore of San Francisco, California.” Tectonophysics 457 (3-4): 209-223. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2008.06.011

Sloan, Doris. 2006. Geology of the San Francisco Bay Region. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wesnousky, Steven G. 2005. “The San Andreas and Walker Lane fault systems, western North America: transpression, transtension, cumulative slip and the structural evolution of a major transform plate boundary.” Journal of Structural Geology 27: 1505–1512.

The History of the San Andreas Fault and Basin and Range – Open Geology online textbook

Discover more from Cal Geographic

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.