Landslides and Mass Movement in California

Once again, California has awoken from a multi-year drought of increasing intensity to an inordinately wet and stormy winter. It may be an early and truncated rainy season, but the return of incessant precipitation and the sound of downpours and gusting south winds is an old familiar friend to lifelong Californians. With the overly wet intermittent winters comes the inevitable landslides and mass movement of our rugged and varied geological terrain.

The terms landslide and mass movement are often used interchangeably. However, mass movement is a designation encompassing numerous geomorphological processes, including landslides. The general technical description for mass movement describes outward or descending gravitational movement of portions of a slope. More specifically, landslides are distinct mass movements that exhibit clear boundaries and have higher rates of movement than any movement on adjacent slopes. There are also several designations of landslides, which will be explored further as we investigate the primary types of mass movement in California.

There are numerous agents of mass movement across California’s landforms and landscapes, including geological, geomorphological, and human causes. These can include weathering or weakness of geologic material, tectonics, erosion, freeze-thaw processes, excavation, deforestation, drainage issues, and many more.

In the winter months the primary agent of earth movement in California is water. From the skies, precipitation causes mass movement induced by ground saturation, flooding, and overflows from blockage or damming on small and large scales. From the ocean, the marine erosional forces of wave and tidal action are major causes of coastal mass movement, cliff collapse, and bluff retreat during our stormy winters as well.

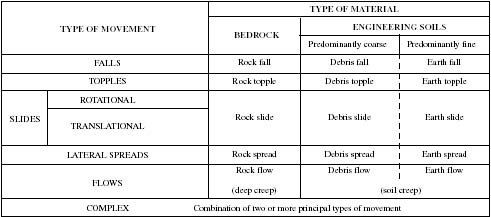

Mass movement is classified by the type of geologic material involved, the mechanism of movement, the rate of the movement, the type of movement, morphology, and other criteria. Major classification systems for mass movement have been developed over the decades, including Varnes 1978; Hutchinson 1988; Cruden and Varnes 1996; and Dikau et al. 1996. A widely accepted classification terminology was developed by the International Geotechnical Societies’ UNESCO Working Party on World Landslide Inventory, 1993. Most, or all, classifications and designations of mass movement occur in California.

The six primary mass movement classification types include Fall, Topple, Slide (rotational and translational), Lateral Spread, Flow, and Complex movement. Each of these six movement types can be composed of one of the three material types: rock, soil, or debris.

The following are brief descriptions of each mass movement classification type, based on summaries by the U.S. Geological Survey, and the International Association of Geomorphologists Encyclopedia of Geomorphology (2013):

A fall (rockfall, debris fall, etc) is a free movement of material from steep, vertical or concave slopes. Falls can form a fan-shaped cone at the base of the slope, not to be confused with talus slopes. Debris and soil falls involve material that is detached from the bedrock.

A topple develops by forward rotation of a mass of rock, debris or soil from a hinge or pivot on a slope. The form of movement is tilting without collapse. Topple failure occurs when detachment of a column transfers the load to a narrow base of weaker rock. Slope height and base width are controlling factors of a topple.

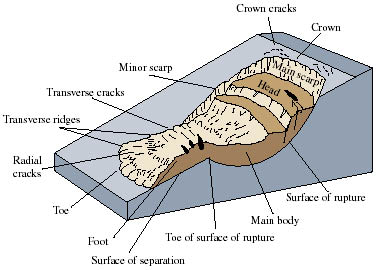

A slide is movement of material along a distinct shear surface, or region of weakness that is defined from more stable underlying and adjacent material. A rotational slide (slump, rotational slip) displays rotational movement over a spoon-shaped shear surface. The slide or mass may break into several discrete blocks. Rotational slides often involve interbedded stronger and weaker materials, clays, and sandstones. Translational slides do not involve rotation or backward tilting, and can involve a single block of material sliding along a planar surface. Translational slides include mud, rock, block, slab, and debris slides.

A lateral spread is the lateral extension and fracturing of a unit of rock, soil, or debris caused by the deformation of underlying softer or liquefied material. Lateral spread can occur on flat surfaces and gentle slopes, can occur rapidly, and often involves liquefaction.

A flow is mass movement in which the individual material particles travel separately within a moving mass. Flows travel in continuous and irreversible motion of materials caused by applied stress. The basic designations of flows are debris flows, soil/mud flows, and rock flows (or rock creep). Where debris and mudflows can be highly destructive and catastrophic mass movements (including debris avalanches and volcanic lahars); rock flow, otherwise known as creep, is so slow its movements are imperceptible, but its affects can be seen in the progressive slumping, curvatures, and deformations of the landscape. Rates of creep deformation can be constant, or can be intermittent, with dormant periods punctuated by short active phases of flow.

A complex is the integration of two or more of the above primary mass movement classifications into one landslide event.

Two areas of particular geologic concern for mass movement in California are landforms and landscapes of the Franciscan Formation (Assemblage, Melange), and California’s coastal bluffs and cliffs. At the leading edge of the North American tectonic plate, much of the Coast Ranges are comprised of the Franciscan Formation; a remnant of the Mesozoic subduction complex and accretionary wedge. Geologic units and materials of the Franciscan Formation are famously sheared, unconsolidated, and weak soils and rock – particularly our state rock, Serpentinite.

Coastal bluffs and cliff faces are often composed of younger, softer, friable sedimentary rocks and soils, such as shale/mudstone, and sandstones of the Cenozoic Era. Marine or coastal bluff erosion and retreat is pronounced along coastlines of the younger Pacific Plate, which stretches from Pacifica in San Mateo County, south to the Mexican border; and in patches from the Marin Coast to Point Arena in the north.

Resources and Further Reading :

Landslides – California Department of Conservation and Geologic Survey

Landslide Types and Processes – USGS

Anderson, Suzanne, and Robert Anderson. 2010. Geomorphology: The Mechanics and Chemistry of Landscapes. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Goudie, A.S. editor. 2013. Encyclopedia of Geomorphology. New York: Routledge

Hampton, M.A., Gary Griggs.2004.“Formation, evolution, and stability of coastal cliffs – status and trends.” Professional Paper 1693. United States Geological Survey

Harden, Deborah. 2004. California Geology. Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Kelsey, Harvey M. 1978. “Earthflows in Francsican mélange, Van Duzen River basin, California.” Geology 6(6): 361-364.

Orme, Antony R. 1991. “Mass movement and seacliff retreat along the southern California coast.” Southern California Academy of Sciences Bulletin 90(2): 58-79.

Wills, C.J. et al.2005.“Geology and slope stability along the Big Sur Coast.” Coast Highway Management Plan, Special Report 185. California Department of Conservation and California Geological Survey

Discover more from Cal Geographic

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.