Serpentinite in California

The State rock of California, commonly referred to as Serpentine, is known for its striking blue-green hue, slick surfaces, and dramatic topography. Serpentinite landscapes form California’s emblematic towering coastal cliffs, Sierran talus slopes, and the pastoral rolling hills of Franciscan formation and Franciscan mélange in the Coast Ranges.

What

Prominent in California, but rare in continental crust worldwide, serpentinite is an ultramafic metamorphic rock of harsh and unique chemistry. Unlike most rocks of the earth’s crust, which are comprised of felsic minerals, ultramafic rocks are constructed primarily of mafic minerals, and are extremely low in silica.

While serpentinite is high in magnesium and iron, as well as the heavy metals nickel, chromium, and cobalt, it is low in calcium, sodium and potassium. Low in the essential nutrients plants need to grow and survive, and high in toxins suppressing growth, serpentinite presents a harsh and restrictive medium that fosters specialized plant adaptations, and the evolution of rare and endemic serpentinite species and habitats in California.

Why

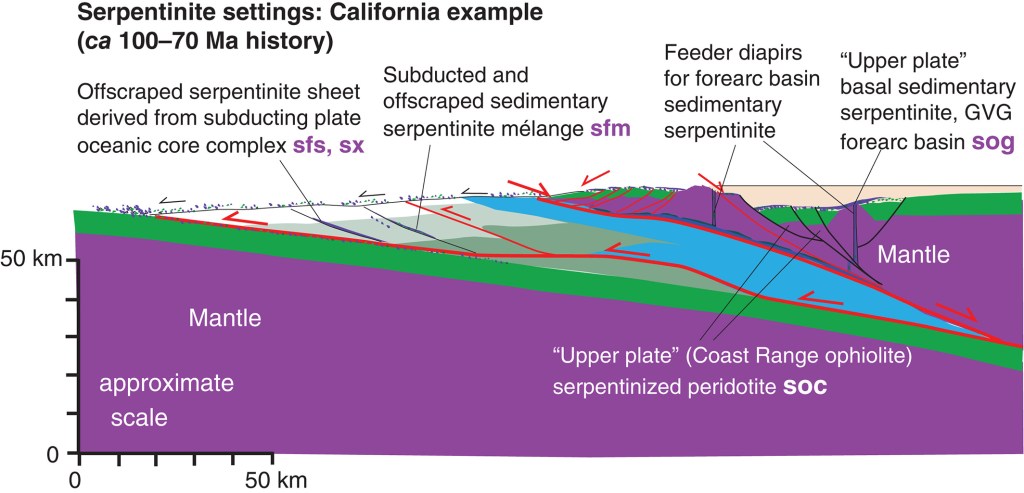

Serpentinite is found in tectonically active landscapes such as subduction zones, where metamorphism readily occurs. A metamorphosed product of peridotite and olivine, serpentinite forms when these common upper mantle minerals are squeezed into the crust above by tectonic action, and come in contact with fluids, such as seawater, wringing out of the subducting slab. This hydration process, known as serpentinization alters the minerals of the mantle rock, producing serpentinite.

Serpentinite and serpentine landforms figure prominently across California, due to its origins as the convergence zone of the prehistoric North American west coast with the subducting oceanic Farallon plate, throughout the Mesozoic and early Cenozoic eras. Serpentinite outcrops in California represent fragments of ancestral ophiolites, sheared mélange deposits within the Franciscan Formation, and constituents of the subduction zone’s accretionary wedge, which today forms the Coast Range.

Where

The outcrops of serpentinite we find throughout the state today are mostly confined to the North American plate eastward of the San Andreas fault zone, and are not found commonly on the younger Pacific plate, which took the place (but not the trajectory) of the subducting oceanic Farallon plate.

Serpentinite in California, is an integral component of accreted terranes and ophiolite suites of the Coast Ranges, the eastern Klamath Mountains, and the northwestern Sierra Nevada.

Geomorphology

Due to its chemistry and structure as a low grade metamorphic rock, Serpentinite is easily erodible, and readily shears, fractures, and breaks down to smaller blocks and grain sizes. Because of this, serpentinite landforms cannot hold their structure at steep angles, and are highly susceptible to slope failure and landslides.

Dramatic and massive slick-faced, blue-green sloping rock faces and boulder-strewn outcrops of serpentinite walls form on the slopes of the Coast Range, and are easily viewed from road cuts and trailside along the Bolinas Ridge and Mount Tamalpais. Talus slopes and gravelly “barrens” are also signature geomorphological features of serpentinite outcrops, contributing to the challenging task plants face establishing habitats in these environments, in addition to the inhospitable chemical conditions of the serpentine soils.

Serpentine soils vary in composition depending on the climatic conditions they develop in. Commonly, serpentinite soils are thin and gravely. In the stabilized bottomlands of serpentine slumps and landslide topography fractured and weathered serpentinite rock forms deep, fine clayey soils, developing an impermeable layer which supports serpentine wetlands such as wet meadows and swales.

Serpentinite rock (parent material) erodes, fractures, and weathers readily. Well-weathered serpentinite breaks down to the size of clay particles, and as serpentinite soils increase in depth, there is an increase in clay particles.

Well-weathered and well-developed serpentinite soils form smectite clay minerals, which swell when hydrated, and tend to absorb and hold large amounts of water. Serpentinite clay particles and soils can also be less developed, and contain more coarse grain fragments, producing well-drained wetland soils.

Peridotite and serpentinite are closely related ultramafic rocks, with almost identical chemical composition, but they differ in mineralogy. As peridotite hydrothermally metamorphoses during serpentinization, the magnesium and silica minerals transform to serpentine minerals, and the iron in peridotite oxidizes to magnetite. These changes result in divergent physical and topographic characteristics between the two rock types. Some of the broad but significant differences between peridotite and serpentinite include color, structure, and soil characteristics.

Peridotite is more structurally sound than serpentinite, while serpentinite is highly erodible, fractures easily, and is much more susceptible to slope failure and landslides. Peridotite usually produces thicker soils with larger rock fragments than the thin soils produced from serpentinite parent material. Due to differences in iron composition and restrained release of pedogenic iron oxides in serpentinite vs. peridotite, the color of peridotite and peridotite topography is generally reddish, while serpentinite presents a grey to blueish-green landscape.

Despite concerted field studies which have highlighted these important distinctions between the two ultramafics, peridotite and serpentinite are commonly lumped together and both identified as serpentine.

To complicate matters, because peridotite and serpentinite are so closely related, and varying degrees of serpentinization of peridotite occur on and within the landscape, soils and geologic bodies of these ultramafic rocks can sometimes present as a transition phase, or a combination of the two.

Interestingly, active serpentinization can be observed in the Coast Ranges of central and northern California. As groundwater comes in contact with exposed peridotites from the Coast Range ophiolite, calcium is released during hydration and produces precipitation of travertine structures in adjacent springs and pools, as a byproduct of the ongoing low grade serpentinzation process. These rarely observed geologic transition zones in their developmental stages, also produce rare and endemic biotic communities and ecosystems.

R. Forest

References

Alexander, E.B., et al. 2011. “Topographic and soil differences from peridotite to serpentinite.” Geomorphology 135: 271–276.

Blake, M.C. et al. 2016. “The Cedars ultramafic mass, Sonoma County, California.” USGS Survey Report, 2012-1164

Harden, Deborah. 2004. California Geology. Upper Saddle River: Pearson

Mooney, Harold and Erika Zavaleta. 2016. Ecosystems of California. Oakland: University of California Press.

Moores, Eldridge, Judith Moores, et al. 2020. Exploring the Berryessa Region: A Geology Tour. Humboldt: Back Country Press.

Morrill, P.L., et al. 2013. “Geochemistry and geobiology of a present-day serpentinization site in California: The Cedars.” Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 109: 222–240

Sloan, Doris. 2006. Geology of the San Francisco Bay Region. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Suzuki, Shino, et al. 2017. “Unusual metabolic diversity of hyperalkaliphilic microbial communities associated with subterranean serpentinization at The Cedars.” ISME Journal 11: 2584-2598.

Discover more from Cal Geographic

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.