R. Forest

Geology and Geomorphology of the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits

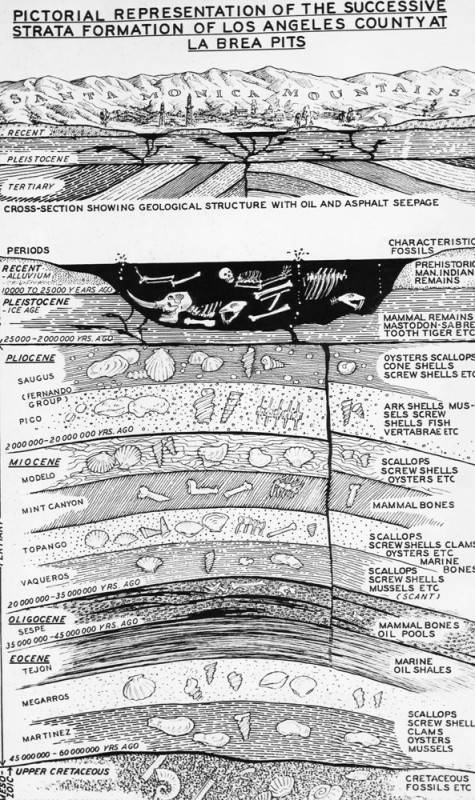

On the chronostratigraphic scale of geologic time, a picture of earth’s past structures, systems, and inhabitants increasingly comes into focus as the ascent out of deep time accelerates toward our current moment on the planet. Geochronologic divisions of life and physical events on earth (based on the appearance and extinctions of life forms; catastrophic events effecting earth’s physiography; plate tectonics; shifts in earth’s magnetic poles; and major climatic events/transitions – such as the unfolding and close of ice ages) are held in the rock record, and illustrated through the geologic/chronostratigraphic time scale.

With the impact of the KT asteroid and resulting mass extinctions, the Mesozoic Era suddenly and catastrophically accedes to the Cenozoic, and Earth’s earliest basic chronological units and divisions on the geologic time scale become further subdivided into Periods and Epochs as our understanding of life on earth deepens and comes more into focus. In the most recent post-KT boundary unit of the geologic time scale, the Quaternary Period encompasses our current Holocene Epoch, and our direct geochronologic lineal ancestor, the Pleistocene Epoch, most commonly referred to as the Ice Age.

The icy life span of the Pleistocene unfurled for more than two and a half million years, extending from approximately 2.6 million to 11, 000 years ago. Prolonged ice ages are usually kicked off when numerous factors of earth’s physics, tectonics, and fluid dynamics align to ignite a cycle of increasing cooling of the planet, as atmospheric and ocean currents switch to a rapid and steady circulation of cold fluids and gasses transported from the poles and delivered out across the planet. With the emergence of the Isthmus of Panama conjoining North and South America; the ascension of the mighty Himalaya and Tibetan Plateau; and the position of orbital Earth within its Milankovitch Cycle, the Pleistocene began.

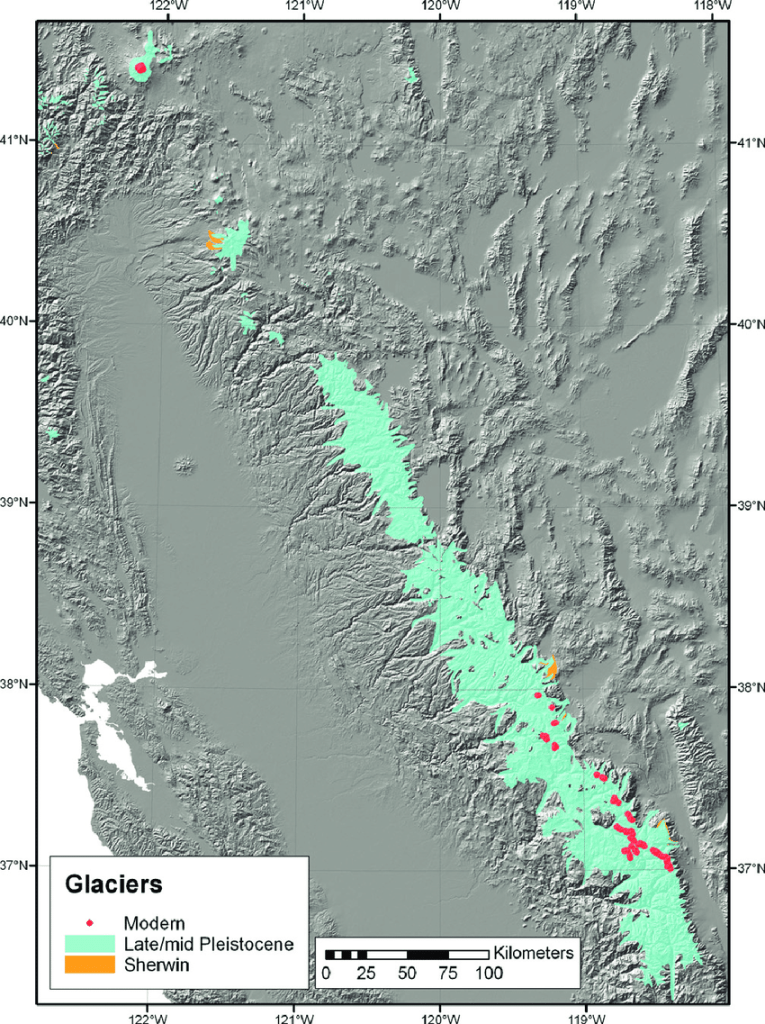

Based on geochronological evidence found in ice core, marine oxygen isotope, loess/paleosol, and glacial till records, it is estimated that Earth experienced at least 20 significant repeated cycles of global glacial advances and retreats during the Pleistocene Epoch, interrupted by cool, stunted summers. Increasing albedo from the swelling glaciers set off a positive feedback loop of declining temperatures and decreasing atmospheric CO2, which further accelerated global cooling and glacial advances.

As with most of Earth during the Pleistocene, California was colder and dryer; however, glaciation and glacial advances were confined to mountainous environments in California, and none of the massive continental glaciers reached this far south. California also experienced extreme shifts in sea level during the Pleistocene, as rapid global glacial advances absorbed and stored ocean waters in ice, resulting in dramatically dropping sea levels and retreating coastlines (eustatic regressions); then transgressing as the glaciers melted during interglacial periods, causing sea level to rise.

The cool thing about the Pleistocene and California, is that California was even in existence. The geographic body that would become California is an extremely young geologic landmass, thus presenting a foreshortened (although uniquely complex) geochronologic record, and sorely lacking in the famous Paleozoic and Mesozoic dinosaur, marine life, and invertebrate fossils which proliferate across other regions of North America. However, by the Pleistocene California was mostly in its current location and geomorphic state, with habitats, plants, and animals we would generally recognize today – and due to its tectonics and unique geomorphology, California would become recognized as the world leader in paleontological contributions from this epoch.

Rancho la Brea: Ranch of the Tar. 18th century Spanish colonists bestowed this significant geologic site with the infamous moniker, and by the 19th century the plentiful visible bones entrained within the La Brea Tar Pits were first understood, not as remains of unlucky wayward livestock, but fossilized specimens of largely unknown prehistoric animals. Now engulfed by the city of Los Angeles, the La Brea Tar Pits are recognized as the largest and most diverse deposit of Pleistocene fossils on Earth. These “Tar Pits” are seeps of asphalt: breeched reservoirs of crude oil held within tightly compacted, and sometimes brittle sedimentary rock formations – formed by tectonic stresses of the natal San Andreas system, then exhumed and exposed for the past 60,000 years.

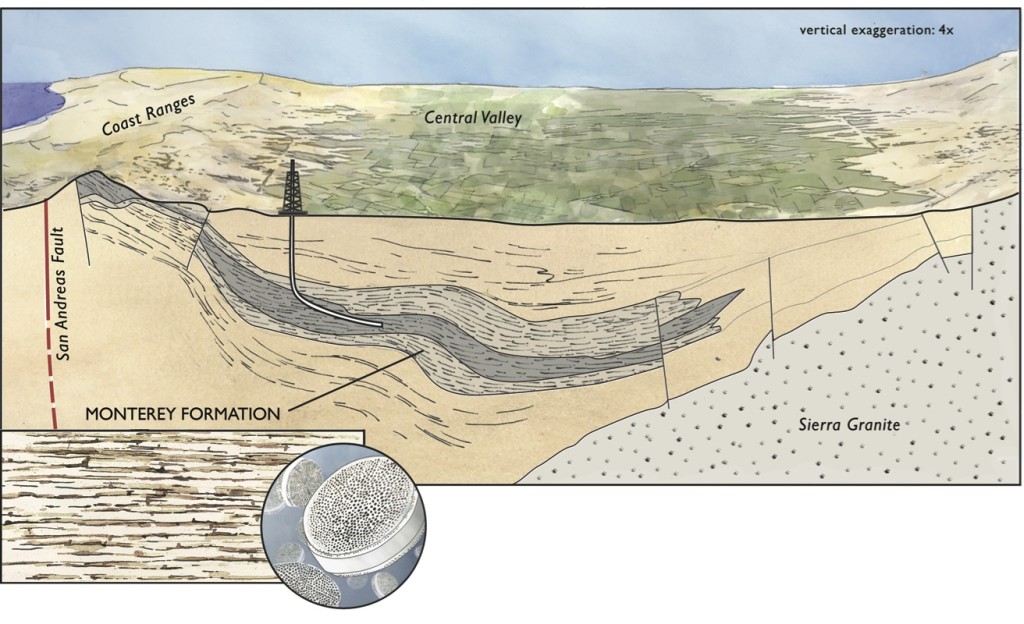

As the Farallon Plate subducted beneath North America’s western edge, and finally the mid-ocean spreading center with it, the mighty northwest rotating Pacific Plate made contact with the continental margin, and the San Andreas transform system was born 20 to 30 million years ago. With the right lateral transform grinding of the fault system, transtensional forces pulled-apart chunks of the coastal margin, creating grabens, drop down basins, and in some cases bays and seaways. Over tens of millions of years, one such seaway opened up near what is now the Los Angeles Basin.

Diagrams of the Monterey Formation in California

In the Miocene Epoch colder ocean temperatures and high diffused silica content in the oceans gave rise to the proliferation of tiny silica-shelled diatomaceous algae, or diatoms. As San Andreas tectonics deepened the marine basin, massive seafloor deposits of mud and silt were becoming the sedimentary rock of the Monterey Formation, and simultaneously collecting layers of diatoms for millennia, encasing the algae under tremendous pressure and some heat, resulting in the formation of massive deposits and reservoirs of hydrocarbons (petroleum). Ongoing tectonic forces of the San Andreas system continue to shift, and expose these reservoirs.

The Salt Lake Oil Field is one of several hydrocarbon reservoirs underlying the Los Angeles Basin today, and is the source of the petroleum seeps at La Brea. It has been extensively drilled since 1902, and is still tapped to this day, despite underlying an extremely dense urban setting. The La Brea Tar Pits seep forth from the Salt Lake Oil Field reservoir at a small tectonic fault of the San Andreas system, known as the 6th Street Fault. Educational materials from the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum mention the Monterey Formation as the source of the Salt Lake Oil Field and La Brea petroleum reservoirs, however, several other sedimentary formations found within the Los Angeles Basin in the vicinity of the Salt Lake Oil Field overlap with the Monterey Formation and also contain hydrocarbon deposits, including, the Puente, Repetto, and Modelo Formations.. and probably others.

Over four million fossil specimens have been recovered from La Brea. These specimens are particularly well preserved by the asphalt, which saturates and encases the biologic material in an anaerobic state, isolating the material from the elements, protecting it from decomposers, and even preserving biologic material on the specimen including collagen. The age of fossilized specimens recovered at La Brea spans from approximately 10,000 to 40,000 years of age, and includes birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish, invertebrates, insects, and plant material. Leading theories propose that the asphalt seeps were usually cloaked by a layer of water and plant debris, resembling ponds, thus luring, entrapping, and killing unsuspecting animals of all sizes for tens of thousands of years, as well as the predators and scavengers that followed the dead and dying.

The fluid asphaltic environment of La Brea Tar Pits not only preserves bones, but also disarticulates and scatters skeletal segments as the mobile viscous medium mixes and overturns with time. This complicates the importance of taphonomic stratigraphic aging of the depositional environment, and of the specimens themselves. Taphonomic patterns within stratigraphic sequences can help determine historic biogeography, past environmental conditions, and even extinction events, but sequences and patterns are disrupted in tar pits, so other aging techniques are required.

New and more precise geochemical analysis and carbon dating techniques have been developed for La Brea specimens, and involve analyzing stable isotope signatures, and removal of petroleum molecules from specimens in order to test isolated collagen samples. These, coupled with the sheer volume and richness of the La Brea fossil collection, aid in the reconstruction of past populations and environmental conditions.

Based on the unique geological setting and geomorphic landscape of the La Brea Tar Pits, and 148 years of excavations and studies, hundreds of scientific papers have been published from work at La Brea, spanning the topics of paleontology, geology, biology, botany, evolution, archaeology, extinctions, past environments, and climate change – which we explore in, California’s Pleistocene Megafauna and the Roll of Climate Change in Extinction: The Younger Dryas, the Rise of Wildfire, and the end of an Epoch

References

Alan, W. A., et al. 1991. “Geochemistry of Los Angeles Basin Oil and Gas Systems.” AAPG Special Volumes – Active Margin Basins, A135: 197-219.

Atwater, Tanya. Animation: “Ice Age Earth and Effects of Sea Level Changes”, http://emvc.geol.ucsb.edu/1_DownloadPage/Download_Page.html

Baron, John A., 1986. “Paleoceanographic and tectonic controls on deposition of the Monterey formation and related siliceous rocks in California.” Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecolgy, 54(1): 27-45.

Bilodeau, W.L., et. al., 2007. “Geology of Los Angeles, California, United States of America.” Environmental and Engineering Geoscience 13(2): 99-160.

Bodnar, Robert J., 1990. “Petroleum migration in the Miocene Monterey Formation, California, USA: constraints from fluid-inclusion studies.” Mineralogical Magazine, 375(54): 295-304.

Gilbert, J. Z., 1927. “The bone drift in the tar beds of Rancho La Brea.” Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, 26(3): 59-66.

Harris, John M. ed, 2015. “La Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas.” Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Science Series 42.

Marcus, Leslie F., Geoffrey Woodard 1973. “Rancho La Brea Fossil Deposits: A Re-Evaluation from Stratigraphic and Geological Evidence.” Journal of Paleontology 41(1): 54-69.

Wright, Tom, 2009. “Geological setting of the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits.” AAPG Petroleum Geology of Coastal Southern California.

Discover more from Cal Geographic

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.