California’s Pleistocene Megafauna and the Role of Climate Change in Extinction: The Younger Dryas, the Rise of Wildfire, and the end of an Epoch

The icy life span of the Pleistocene Epoch, commonly referred to as the Ice Age, unfurled for more than two and a half million years, from 2.6 million to 11,000 years ago. The geographic and geologic engines that predestined and ignited our most recent ancestral ice age are reviewed in detail in Cal Geographic’s summary, The Geology and Geomorphology of the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits

A relatively rapid cycle of glacial advances and retreats pulsed in increasing duration and intensity throughout the Pleistocene. While the entire earth experienced cooler climates, much of the upper and lower latitudes, as well as mountainous regions endured boreal, subarctic, and arctic climatic conditions throughout the Pleistocene. The majority of this area was subject to total glaciation during the advances.

As glaciers and cold climates advanced, land animal migration routes were closed, populations were isolated from each other, and habitats and food sources pushed equatorward. During interglacial retreats, new migration routes formed, plant and animal population ranges shifted and expanded, and ecosystems such the mammoth steppe, scrublands, and boreal forests marched poleward. In response to the extreme geographic and climatic swings of the Ice Age, large-bodied, cold-adapted migratory mammals were selected to endure.

Rancholabrean Fauna

The Ice Age and megafauna are synonymous in our imaginations; in no small part to California’s outsized contribution to our understanding of the environments and evolutionary biology of the Pleistocene. Beyond charismatic, the megafauna of the Pleistocene captures our imaginations as an extinct and fantastical bestiary of monstrous be-tusked, dagger-clawed, and shaggy giants, fighting for survival in an icy, prehistoric world. Most of it is true, and the gateway to this world is Rancho La Brea in Los Angeles, California.

The La Brea Tar Pits are the largest and most diverse depositional assemblage of late-Pleistocene fossils on earth. Due to the immensity of the fossil flora and fauna discovered at this site, the Rancholabrean Provincial Land Mammal Age was selected as the standard reference to which all other North American late Pleistocene fossil faunas are compared. Based on the unique geological setting of the La Brea Tar Pits, and 148 years of excavations, studies, and advances in specimen aging techniques, hundreds of scientific papers have been published from La Brea, spanning the topics of paleontology, geology, biology, botany, evolution, archaeology, extinctions, past environments, and climate change.

The tar pits are an asphalt seep of a breeched natural petroleum reservoir, along a small active fault line in the hydrocarbon deposit-rich Los Angeles Basin. For 60,000 years plants and animals have become mired in the seep by chance, under pursuit, or for mistaking them as a water source. The plant and animal remains are then very slowly subsumed within the petroleum to undergo an extremely efficient and thorough form of taphonomic preservation and fossilization. The age of fossilized specimens recovered at La Brea so far spans from approximately 10,000 to 40,000 years of age, and includes birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish, invertebrates, insects, human remains, and plant material.

Through pollen analysis at La Brea, a clear snapshot of the climate and ecosystems of late-Pleistocene Los Angeles during the last glacial maximum has been discovered to closely resemble the wetter and cooler coastal environment of the Monterey Peninsula today. Pine forests dominated the slopes in Pleistocene Southern California, with stands of mixed evergreen forest, oak woodlands, streamside riparian vegetation, chaparral, and coastal sage scrublands scattered throughout the Los Angeles Basin.

While California’s Miocene-aged, 15 million year-old Mediterranean Climate was somewhat interrupted during the Ice Age, and our signature drought-adapted habitats retreated southward, the cold eastern boundary current that sets up the dry summer/ wet winter cycle prevailed, and still persists in our current epoch. With the persistence of the Mediterranean climate in Southern California throughout the Pleistocene, most of the late Pleistocene fossil specimens (over four million) excavated at the La Brea Tar Pits are of plants and animals that survived the Ice Age, and we would recognize from ecosystems and populations alive today (or near ancestors of current populations). But why did the fantastical Ice Age megafauna of California, discovered through a century of excavations at La Brea, go extinct so recently and so abruptly?

Cooling and the Younger Dryas

As the climatic pendulum delivering millions of years of glaciations slowed, and the Last Glacial Maximum of the Pleistocene gave way to the interglacial Holocene Epoch, an abrupt and rapid cooling event, known as the Younger Dryas, mysteriously interrupted the trajectory of Earth’s warming in the northern hemisphere. The Younger Dryas was short lived, but it was an ominous curtain call on the Pleistocene. As plant and animal communities were adapting to or declining at the transition to a warm, dry Holocene climate regime, the sudden cooling ushered in yet another glacial advance and a reinvigorated ice age, out of place and time.

The Younger Dryas stadial event is named for Dryas octopetala, a tiny flowering shrub in the rose family, associated with arctic tundra and post-glaciated alpine habitats in the northern hemisphere, found in profusion in pollen core samples associated with the Younger Dryas time frame. The Younger Dryas is estimated to have lasted 1100-1300 years in duration, occurred from about 12,900 to 11,700 years ago, and is preceded by two other notable, but shorter, stadials in the late Pleistocene: the Older Dryas and the Oldest Dryas.

Commencing and terminating abruptly, the leading theory (and there are many) as to what caused the Younger Dryas involves the interruption of the Atlantic Ocean’s circulation systems, when a massive inundation of glacial meltwater from the retreating North American-Laurentide ice sheet entered the north Atlantic, and/or the Arctic Ocean. This could have involved one or more catastrophic flooding events when weakening ice dams blocking giant Pleistocene meltwater lakes failed. Evidence supports a scenario in which an influx of fresh meltwater disrupted the ocean’s thermohaline circulation, slowing the Atlantic meridional circulation, and leading to rapid oceanic and atmospheric cooling in the northern hemisphere (and warming in the southern hemisphere).

Evidence of the existence and duration of the Younger Dryas has been obtained from many sources worldwide, including pollen and sediment core samples, ice cores, oxygen isotope analyses, tree ring data, stalagmite growth data, radiocarbon dating of fossils, and from loess deposits… just to name a few. A prominent relict and marker of the Younger Dryas is the Black Mat layer, found stratigraphically across the earth (including in deposits on California’s northern Channel Islands).

At the Pleistocene-Holocene transition period of deglaciation, The Younger Dryas Black Mat shows up in earth’s chronostratigraphic record as a mostly dark colored, organic-rich layer of aquolls, paleosols, diatomites, and algal mats. This striking stratigraphic component indicates a markedly colder and wetter period of high water tables and increased cold-climate wetland ecosystem development, bookended by much warmer and dryer regimes. According to radiocarbon data, The Younger Dryas Black Mat also coincides stratigraphically with the sudden termination of the remnants of the Pleistocene Rancholabrean megafauna.

The beginning of the Younger Dryas stadial, along with the catastrophic extinction of Rancholabrean fauna have been established as the markers of the geogchronologic close of the Pleistocene. Evidence of the paleo-indigenous Clovis culture of North America also ceased from the stratigraphic record at this time. No single cause has been identified as the major contributor to the demise of the Rancholabrean Pleistocene megafauna. Most scientific investigations propose a combination of lethal mechanisms, including prolonged drought, the shock of the sudden onset of a renewed ice age, and efficient hunting strategies of paleo human populations as the deferred conclusion.

While it is highly probable that many Pleistocene megafauna species actually declined toward extinction more gradually over a longer time period, stratigraphic analysis and dating methods have shown that the prominent ice age populations of mammoths, mastodons, horses, camels, dire wolves, American lions, short-faced bears, sloths, and tapirs all terminated suddenly near the onset of the Younger Dryas. Only continued excavations and more precise dating methods can clarify the cause, or causes, of the extinction of the Rancholabrean fauna: Did hunting pressures at the onslaught of a frigid climatic whiplash exterminate the megafauna? Or were the Ice Age mammals already gone, and yet another catastrophic mechanism was to blame?

Warming and the Rise of Wildfire

The glacial advances of the Pleistocene waned with the retreat of the Last Glacial Maximum approximately 20,000 years before present, and a series of shorter stadials, alternating with interstadial warming events, ushered in the Holocene. A pronounced period of late deglaciation known as the Bolling-Allerod Warming (interstadial) began 14,700 years ago as midnight fell on the Pleistocene. The Bolling-Allerod commenced at the closing of the Older Dryas stadial, and ended abruptly 12,900 years ago at the onset of the Younger Dryas.

The Bolling-Allerod brought accelerated global warming and drying not seen previously in the geochronologic record of the Pleistocene. While late-Pleistocene extinctions of Ice Age megafauna in North America occurred throughout the Younger Dryas stadial, a new study from researchers at Rancho La Brea pinpoints a stark and dramatic finality that befell the Rancholabrean megafauna of Southern California before this, during the Bolling-Allerod Warming.

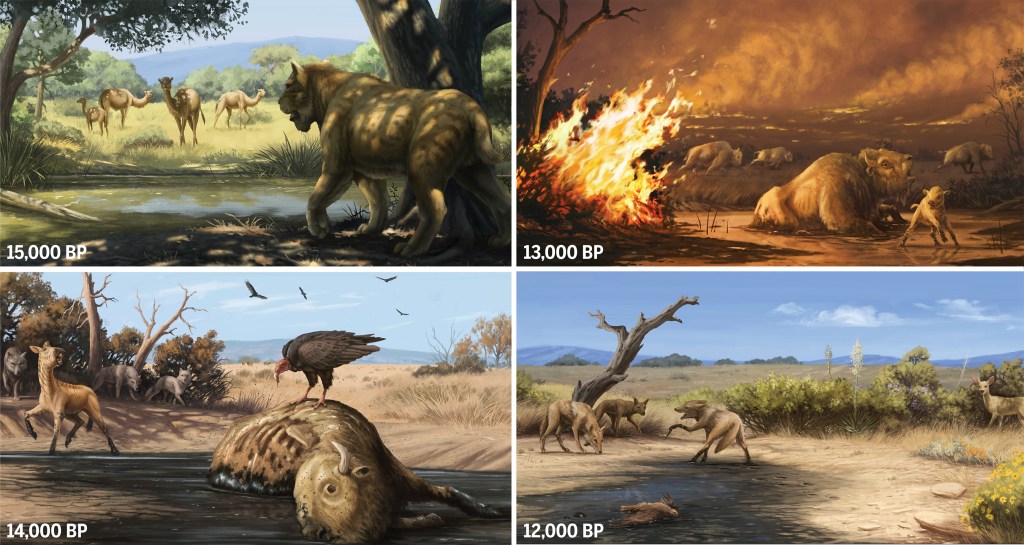

Data collected through precision radio carbon dating of collagen from 172 fossil specimens at Rancho La Brea (of the eight most common Rancholabrean species: Saber-toothed cat [Smilodon fatalis], Dire wolf [Aenocyon dirus], Coyote [Canis latrans], American lion [Panthera atrox], Ancient bison [Bison antiquus], Western horse [Equus occidentalis], Harlan’s ground sloth [Paramylodon harlani], and Camel [Camelops hesternus]), modeled with current paleo-climate data, paleo-vegetation records, and anthropological demographic data, a clear picture of the interrelationship between climate aridification, wildfire, humans, and extinction comes into focus.

Findings from the Rancho La Brea study are bolstered by coincident evidence from sediment core analysis of prehistoric wildfire regimes at Lake Elsinore (roughly 70 miles southeast of Rancho La Brea, in Southern California). The two studies together reveal a complete extinction of the Rancholabrean megafauna in Southern California within a 300 year period of mega-drought conditions, a rapid ecosystem shift from woodlands to chaparral ecosystems, increased human presence, and the increased occurrence of extensive and prolonged wildfire.

Persistent and aggressive wildfire alters the function and structure of ecosystems, hydrologic systems, landforms, and climate. This centuries-long late Pleistocene wildfire regime in Southern California undoubtedly accelerated the transformation of the landscape from woodland to the Mediterranean scrublands we know today.

Debate remains how much of an influence humans had on the Pleistocene landscape of Southern California, and if the increase in wildfire was in fact due to human ignitions. However, it is apparent that human occupation and wildfire increased simultaneously in late Pleistocene California. Paleoclimate data from previous pre-human warming and drying periods in California do not show the same wildfire regimes or catastrophic consequences.

California Pleistocene Fauna and Ecosystems Today

Today, in our interglacial of the Holocene epoch, we are still rebounding from the last glacial maximum, and much of the biogeography and geomorphology of our state reflects and harbors the living landscapes of the Pleistocene. For further exploration, below are links to a sampling of some of these dynamic and fragile reminders of the Ice Age in California. Additionally, it is significant to note that we, Homo sapiens, are of the Pleistocene as well. Along with other paleo-floral and faunal communities, our species evolved and migrated throughout the very recent Ice Age:

We are Pleistocene Fauna: Hominid evolution in the Pleistocene 1

We are Pleistocene Fauna: Hominid evolution in the Pleistocene 2

Human migrations in the Pleistocene 1

Human migrations in the Pleistocene 2

Earliest human records in California 1

Earliest human records in California 2

Rancho La Brea Fossil Collections

References:

Chenga, H., et al. 2020. “Timing and structure of the Younger Dryas event and its underlying climate dynamics.” PNAS 117:38.

Coltrain, J.B., et al. 2004.“Rancho La Brea stable isotope biogeochemistry and its implications for the palaeoecology of late Pleistocene, coastal southern California.” Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 205:199–219.

Cowart, D.A., 2014. “Paleoenvironmental Change in Central California in the Late Pleistocene and Holocene: Impacts of Climate Change and Human Land Use on Vegetation and Fire Regimes.” UC Berkeley Dissertation

Emanuel M. Fonseca, E.M., et al. 2023. “Pleistocene glaciations caused the latitudinal gradient ofvwithin-species genetic diversity.” Evolution Letters 7(5):331–338.

Frederik V. Seersholm, F.V., et al. 2020. “Rapid range shifts and megafaunal extinctions associated with late Pleistocene climate change.” Nature Communications 11:2770.

Fuller, Benjamim T., et al. 2014. “Ultrafiltration for asphalt removal from bone collagen for radiocarbon dating and isotopic analysis of Pleistocene fauna at the tar pits of Rancho La Brea, Los Angeles, California.” Quaternary Geochronology 22:85-98.

Haynes, C.V., 2008. “Younger Dryas black mats and the Rancholabrean termination in North America.” PNAS 105(18).

Monteath, J. et al. 2023. “Relict permafrost preserves megafauna, insects, pollen, soils and pore-ice isotopes of the mammoth steppe and its collapse in central Yukon.” Quaternary Science Reviews 299.

Okeefe, F.R., et al. 2023. “Pre–Younger Dryas megafaunal extirpation at Rancho La Brea linked to fire-driven state shift.” Science 381 (6659).

Parkman, E.B., 2006. “The California Serengetti: Two Hypotheses Regarding the Pleistocene Paleoecology of the San Francisco Bay Area.” California State Parks publication 1-49.

Smith, F.A., et al. 2023. “After the mammoths: The ecological legacy of late Pleistocene megafauna extinctions.” Cambridge Prisms: Extinction 1:1–23

Trayler, R.B., et al, 2015.”Inland California during the Pleistocene—Megafaunal stable isotope records reveal new paleoecological and paleoenvironmental insights.” Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 437:132-140.

Zimov, S.A., et al. 2012.”Mammoth steppe: a high-productivity phenomenon.” Quaternary Science Reviews 57:26-45.

Discover more from Cal Geographic

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.