Cal Geographic Maritime Journal

An informal collection of journal posts and photo albums highlighting California’s maritime history

A lighthearted collage of coastal culture and familial connections

And an archive of classic posts from the former Coastal Zone CA blog

Richard Henry Dana’s, Two Years Before the Mast

In 1834, Richard Henry Dana left school and a life of privilege behind in Boston to sign-on as a common sailor aboard the merchant ship, Pilgrim. He sought adventure and physical rigor in an attempt to combat a degenerative illness, but was instantly faced with the brutal reality of the grueling and unending labor, hardships, and hazards of life as a seaman. His intense desire to prove himself a worthy sailor and friend to his crewmates, coupled with meticulous and eloquent daily record keeping of his enfolding two year journey, provided the world with a unique and invaluable record of the true, unromantic realities of life at sea.

Two Years Before the Mast was the first detailed account of the common sailor’s plight, and it served to enlighten young men across the world to the unromantic realities they would face if choosing a life aboard. And for those of us concerned with history and the preservation of the coast, Two Years Before the Mast provides a priceless glimpse into the landscapes and cultures of pre-Gold Rush, early colonial California. At the close of his California voyage, Dana completed his law degree at Harvard and dedicated his life to the advocacy and legal protection of common sailors. Herman Melville was among the many inspired by Dana’s unique literary accomplishment, and in 1841 he too boarded a vessel to research and live the whaling life for himself, and subsequently penned Moby Dick.

The typical years-long trade route Richard Henry Dana experienced, ping-ponged up and down the California coast, allowing crew to become intimate with the wild California landscape, weather patterns, seasonal indicators, maritime hazards and shortcuts, the nuances of tides, bays, and the myriad techniques of landing every harbor and beach. Working aboard the Pilgrim and then the Alert, acquiring cattle hides from the Spanish missions and settlements up and down the coast, Dana’s undulating longitudinal route took him to: Santa Barbara, Monterey, Santa Barbara, San Pedro (Los Angeles), San Diego, San Pedro, Santa Barbara, San Pedro, San Juan (Capistrano/Dana Point), San Diego, San Pedro, Santa Barbara, San Diego, San Juan, San Pedro, Santa Barbara, San Francisco, Monterey, Santa Barbara, San Pedro, San Diego, Santa Barbara, San Pedro, and finally San Diego before setting sail south for Cape Horn and home.

I researched the exact present day locations of some of Dana’s 188 year old landing sites, and visited and photographed the sites as they appear today. The following are select passages from Two Years Before the Mast, describing Richard Henry Dana’s first encounters, landings, and adventures at some of these now beloved and populous cities, sites, and bays. All header photos taken by Rowena Forest, and correspond with the passage location:

First landing in California, first impressions of Santa Barbara, and the earliest record of surfing in California 188 years ago:

January 14th, 1835 – Santa Barbara

It was a beautiful day, and so warm that we wore straw hats, duck trousers, and all the summer gear. As this was midwinter it spoke well for the climate, and we afterward found that the thermometer never fell to the freezing point throughout the winter, and that there was very little difference between the seasons, except that during a long period of rainy and southeasterly weather, thick clothes were not uncomfortable.

The large bay lay about us, nearly smooth as there was hardly a breath of wind stirring, though the boat’s crew who went ashore told us that the long ground swell broke into ta heavy surf on the beach… In the middle of this crescent, directly opposite the anchoring ground, lie the mission and town of Santa Barbara, on a low plain, but little above the level of the sea, covered with grass, though entirely without trees, and surrounded on three sides by an amphitheater of mountains, which slant off to the distance of fifteen or twenty miles. The mission stands a little back of the town and is a large building, or rather collection of buildings, in the center of which is a high tower, with a belfry of five bells. The whole, being plastered, makes quite a show at a distance and is the mark by which vessels come to anchor… Just before sundown, the mate ordered a boat’s crew ashore, and I was one of the number. We passed under the stern of the English brig, and had a long pull ashore.

I shall never forget the impression which our first landing on the beach of California made upon me. The sun had just gone down; it was getting dusky; the damp night wind was beginning to blow, and the heavy swell of the Pacific was setting in, and breaking in loud and high “combers” upon the beach. We lay on our oars in the swell, just outside the surf, waiting for a good chance to run in, when a boat, which had put off from the Ayacucho, came alongside of us, with a crew of Sandwich Islanders, talking in their tongue. They knew that we were novices in this kind of boating and waited to see us go in. The second mate, however, who steered our boat, determined to have the advantage of their experience, and would not go in first. Finding, at length, how matters stood, they gave a shout, and taking advantage of a greater comber which came swelling in, rearing its head, and lifting up the sterns of our boats nearly perpendicular, and again dropping them in the trough, they gave three or four long and strong pulls, and went in on top of the great wave, throwing their oars overboard, and as far from the boat as they could throw them, and jumping out the instant the boat touched the beach, they seized hold of her by the gunwale, on each side, and ran her up high and dry upon the sand. We saw, at once, how the thing was to be done, and also the necessity of keeping the boat stern out to the sea; for the instant the seas should strike upon her broadside or quarter, she would be driven u broadside on, and capsized…

The sand of the beach began to be cold to our bare feet; the frogs set up their croaking in the marshes and one solitary owl, from the end of the distant point, gave out his melancholy note, mellowed by the distance, and we began to think that I was high time for “the old man,” as a shipmaster is commonly called, to come down..

Monterey

The bay of Monterey is wide at the entrance, being about twenty-four miles between the two points, Ano Nuevo at the north, and Pinos at the south, but narrows gradually as you approach the town, which is the whole depth of the bay. The shores are extremely well wooded (the pine abounding upon them), and as it was now the rainy season, everything was as green as nature could make it – the grass, the leaves, and all; the birds were singing in the woods, and great numbers of wild fowl were flying over our heads. Here we could lie safe from the southeasters. We came to anchor within two cable lengths of the shore, and the town lay directly before us, making a very pretty appearance; its houses being of whitewashed adobe, which gives a much better effect than those of Santa Barbara, which are mostly left a mud color. The red tiles too, on the roofs, contrasted well with the white sides, and with the extreme green-ness of the lawn upon which the houses – about a hundred in number – were dotted about, here and there, irregularly. There are in this place, and in every other town which I saw in California, no streets nor fences (except that here and there a small patch might be fenced in for a garden), so that the houses are placed at random upon the green. This, as they are of one story, and of the cottage form, gives them a pretty effect when seen from a little distance.

The Californians are an idle, thriftless people, and can make nothing for themselves, The country abounds in grapes, yet they buy, at a great price, bad wine made in Boston and brought round by us, and retail it among themselves at a real (12 and a half cents) by the small wineglass.

Impressions of the barren and deserted coast between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles (unimaginable), first sight of the mouth of the Los Angeles Basin, and landing at San Pedro/LA Harbor:

Leaving Santa Barbara, we coasted along down, the country appearing level or moderately uneven, and for the most part, sandy and treeless; until doubling a high sandy point, we let go our anchor at a distance of three or three and a half miles from shore. It was like a vessel bound to St John’s, Newfoundland, coming to anchor on the Grand Banks; for the shore, being low, appeared to be at a greater distance than it actually was, and we thought we might as well have stayed at Santa Barbara and sent our boat down for the hides. The land was of a clayey quality, and , as far as the eye could reach, entirely bare of trees and even shrubs; and there was no sign of a town – knot even a house to be seen, What brought us into such a place, we could not conceive, No sooner had we come to anchor, than the slip rope, and the other preparations for southeasters, were got ready; and there was reason enough for it , for we lay exposed to every wind that could blow, except the northerly winds, and they came over a flat country with a rake of more than a league of water, As soon as everything was snug on board, the boat was lowered and we pulled ashore, our new officer, who had been several times in the port before, taking the place of steersman, As we drew in, we found the tide low, and the rocks and stones, covered with kelp and seaweed, lying bare for the distance of nearly an eighth of a mile.

Leaving the boat, and picking our way barefooted over these, we came to what is called the landing place, at high-water mark, The soil was, as it appeared at first, loose and clayey, and except the stalk of the mustard plant, there was no vegetation… I also learned, to my surprise, that the desolate-looking place we were in furnished more hides than any port on the coast. It was the only port for a distance of eighty miles, and about thirty miles in the interior was a fine plane country, filled with herds of cattle, in the center of which was the Pueblo de Los Angeles – the largest town in California – and several of the wealthiest missions; to all of which San Pedro was the seaport.The coyotes (a wild animal of a nature and appearance between that of the fox and the wolf) set up their sharp, quick bark, and two owls, at the end of the distant points running out into the bay, on different sides of the hill where I lay, kept up their alternate dismal notes. I had heard the sound before at night, but did not know what it was, until one of the men, who came down to look at my quarters told me it was the owl. Mellowed by the distance, and heard alone, at night it was a most melancholy and boding sound. Through nearly all the night they kept it up, answering one another slowly at regular intervals, This was relieved by the noisy coyotes, some of which came quite near to my quarters, and were not very pleasant neighbors.

First passage into San Diego Bay, and the following months’ encounters and stories on a San Diego beach:

At sunset on the second day we had a large and well-wooded headland directly before us, behind which lay the little harbor of San Diego. We were becalmed off this point all night, but the next morning, which was Saturday, the fourteenth of March, having a good breeze, we stood round the point, and, hauling our wind, brought the little harbor, which is rather the outlet of a small river, right before us. Everyone was desirous to get a view of the new place. A chain of high hills, beginning at the point (which was on our larboard hand coming in), protected the harbor on the north and west, and ran off into the interior, as far as the eye could reach. On the other sides the land was low and green, but without trees. The entrance is so narrow as to admit but one vessel at a time, the current swift, and the channel runs so near to a low, stony point, that the ship’s sides appeared almost to touch it. There was no town in sight, but on the smooth sand beach, abreast, and within a cable’s length of which three vessels lay moored, were four large houses, built of rough boards, and looking like the great barns in which ice is stored on the borders of the large ponds near Boston, with piles of hides standing round them, and men in red shirts and large straw hats walking in and out of the doors. These were the hide houses…

All the hide houses on the beach but ours were shut up, and the Sandwich Islanders, a dozen or twenty in number, who had worked for the other vessels, and been paid off when they sailed, were living on the beach, keeping up a grand carnival. There was a large oven on the beach, which, it seems, had been built by a Russian discovery ship that had been on the coast a few years ago, for baking her bread. This, the Sandwich Islanders took possession of, and had kept ever since, undisturbed… There they lived, having a grand time, and caring for nobody…

Here was a change in my life as complete as it had been sudden. In the twinkling of an eye I was transformed from a sailor into a beachcomber and a hide curer; yet the novelty and the comparative independence of the life were not unpleasant…

I ought, perhaps, to except the dogs, for they were an important part of our settlement. Some of the first vessels brought dogs out with them, who for convenience, were left ashore, and there multiplied, until they came to be a great people.. While I was on the beach, the average number was about forty, and probably an equal, or greater, number are drowned, or killed in some other way, every year. They are very useful in guarding the beach. Hogs and a few chickens were the rest of the animal tribe, and formed, like the dogs, a common company..

First impressions of San Juan Capistrano area and Dana Point:

Coasting along on a quiet shore of the Pacific, we came to anchor in twenty fathoms water, almost out at sea, as it were, and directly abreast of a steep hill which overhung the water, and was twice as high as our royal masthead. We had heard much of this place from the Lagoda’s crew, who said it was the worst place in California. The shore is rocky, and directly exposed to the southeast, so that vessels are obliged to slip and run for their lives on the first sign of a gale; and late as it was in the season, we got up our slip rope and gear, though we meant to stay only twenty four hours. We pulled the agent ashore and were ordered to wait for him, while he took a circuitous way round the hill to the mission, which was hidden behind it. We were glad of the opportunity to examine this singular place, and hauling the boat up, and making her well fast, took different directions up and down the beach, to explore it. San Juan is the only romantic spot on the coast. The country here for several miles is high tableland, running boldly to the shore, and breaking off in a steep cliff, at the foot of which the waters of the Pacific are constantly dashing. For several miles the water washes the very base of the hill, or breaks upon ledges and fragments of rocks which run out into the sea. Just where we landed was a small cove, or bight, which gave us, at high tide, a few square feet of sand beach between the sea and the bottom of the hill. Directly before us rose the perpendicular height of four or five hundred feet. How we were to get hides down, or goods up, upon the tableland on which the mission was situated was more than we could tell… Beside, there was a grandeur in everything around, which gave a solemnity to the scene, a silence and solitariness which affected every part! Not a human being but ourselves for miles, and no sound heard but the pulsations of the great Pacific!

One or two other carts were coming slowly on from the mission, and the captain told us to begin and throw the hides down. This, then, was the way they were to be got down – thrown down, one at a time, a distance of four hundred feet! This was doing the business on a great scale. Standing on the edge of the hill ,and looking down the perpendicular height.. Down this height we pitched the hides, throwing them as far out into the air as we could; and as they were all large, stiff, and doubled, like the cover of a book, the wind took them, and they swayed and eddied about, plunging and rising in the air, like a kite when it has broken its string. As it was now low tide, there was no danger of their falling into the water; and as fast as they came to ground, the men below picked them up, and taking them on their heads, walked off with them to the boat. It was really a picturesque sight: the great height, the scaling of the hides, and the continual walking to and fro of the men, who looked like mites on the beach. This was the romance of hide droghing! Some of the hides lodged in cavities under the bank and out of our sight, being directly under us; but by pitching other hides in the same direction, we succeeded in dislodging them. Had they remained there, the captain said he should have sent on board for a couple of pairs of long halyards and got someone to go down for them, It was said that one of the crew of an English brig went down in the same way, a few years before. We looked over, and thought it would not be a welcome task, especially for a few paltry hides; but no one knows what he will do until he is called upon; for six month s afterward, I descended the same place by a pair of topgallant-studding-sail halyards to save half a dozen hides which had lodged there.

First entry into the San Francisco Bay:

…we made a fair wind for San Francisco. This large bay, which lies in latitude 37, 58’, was discovered by Sir Francis Drake, and by him represented to be (as indeed it is) a magnificent bay, containing several good harbors, great depth of water, and surrounded by a fertile and finely wooded country. About thirty miles from the mouth of the bay, and on the southeast side, is a high point, upon which the presidio is built,. Behind this point is the little harbor, or bight, called Yerba Buena, in which trading vessels anchor, and, near it, the Mission of Dolores. There was no other habitation on this side of the bay, except a shanty of rough boards put up by a man named Richardson, who was doing a little trading between the vessels and the Indians… We passed directly under the high cliff on which the presidio is built, and stood into the middle of the bay, from whence we could see small bays making up into the interior, large and beautifully wooded islands, and the mouths of several small rivers. If California ever becomes a prosperous country, this bay will be the center of its prosperity. The abundance of wood and water; the extreme fertility of its shores, the excellence of its climate, which is as near to being perfect as any in the world; and its facilities of navigation, affording the best anchoring grounds in the whole western coast of America – all fit it for a place of great importance. The tide leaving us, we came to anchor near the mouth of the bay, under a high and beautifully sloping hill, upon which herds of hundreds and hundreds of red deer, and the stag, with his high branching antlers, were bounding about, looking at us for a moment, then starting off, affrighted at the noises which we made for the purpose of seeing the variety of their beautiful attitudes and motions.

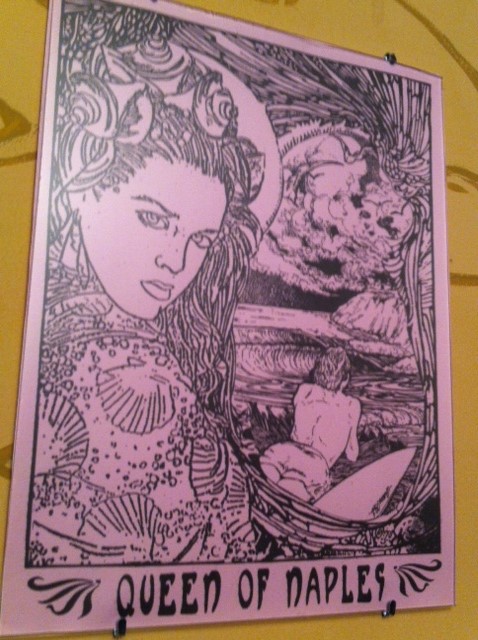

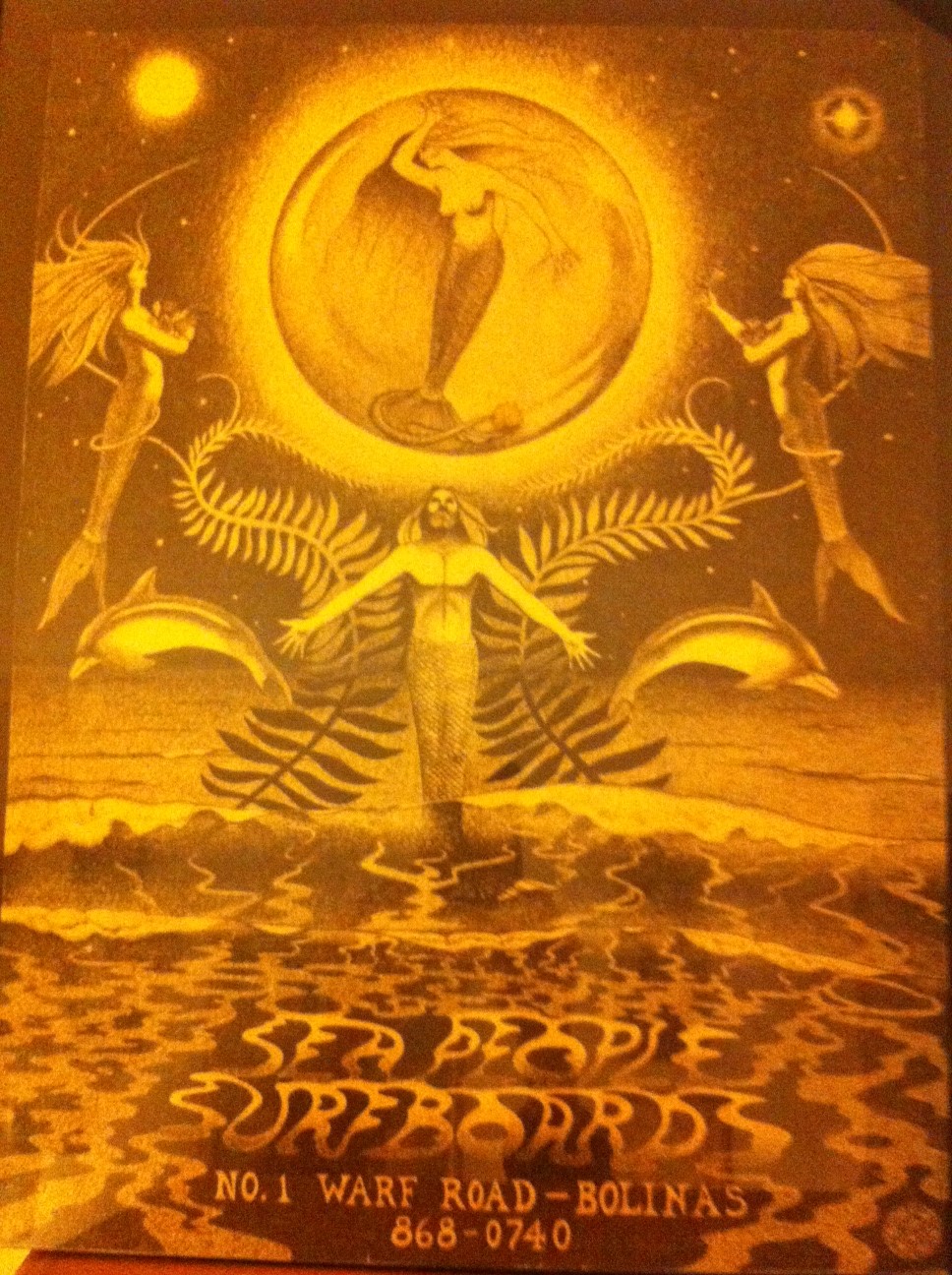

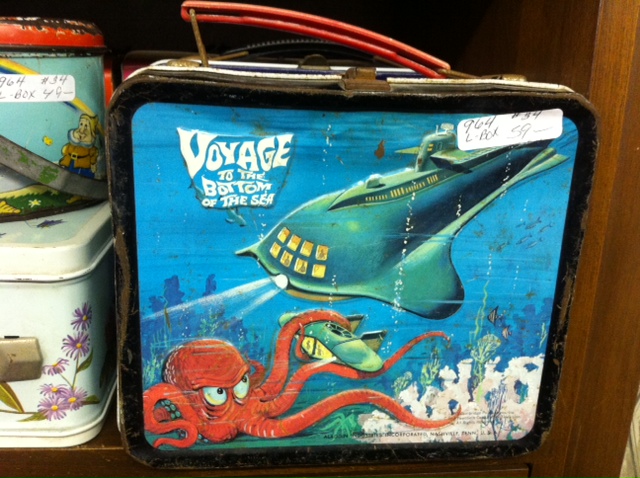

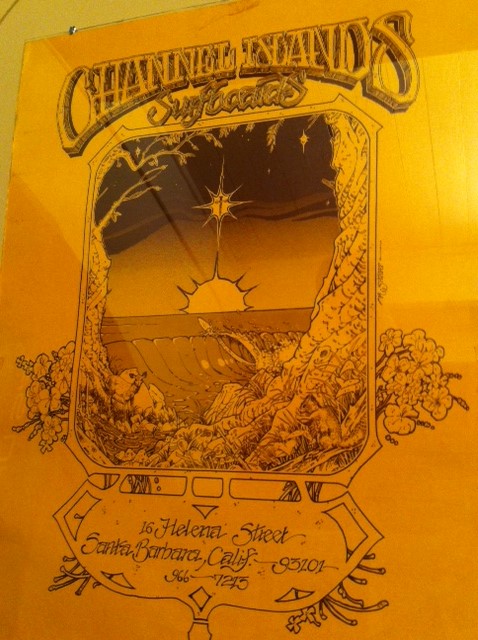

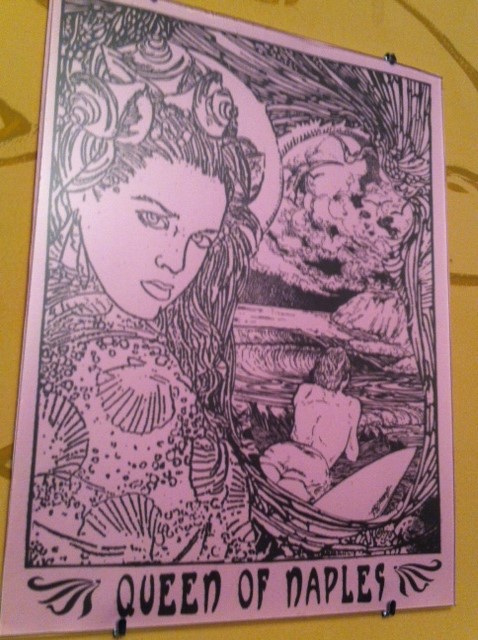

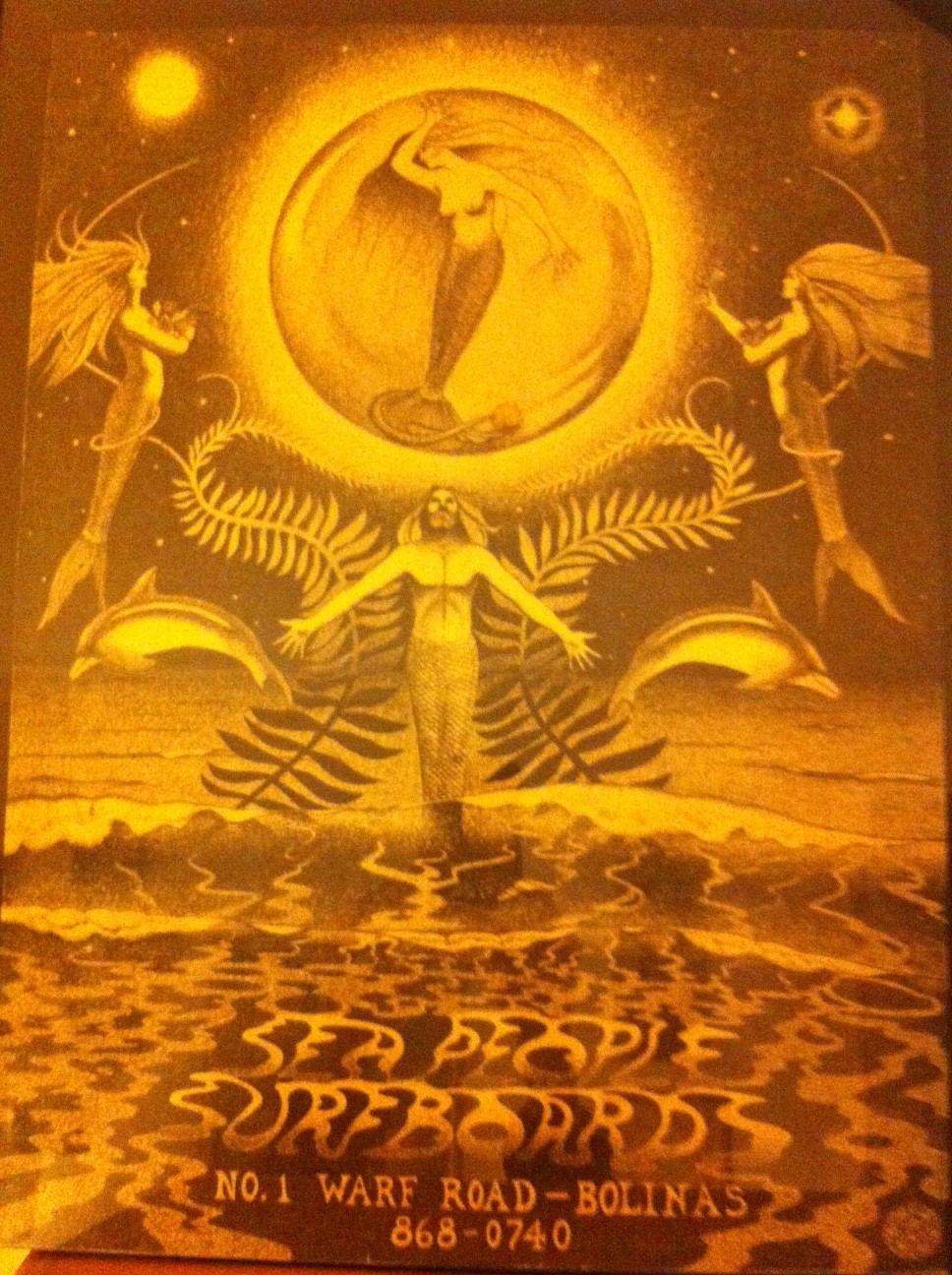

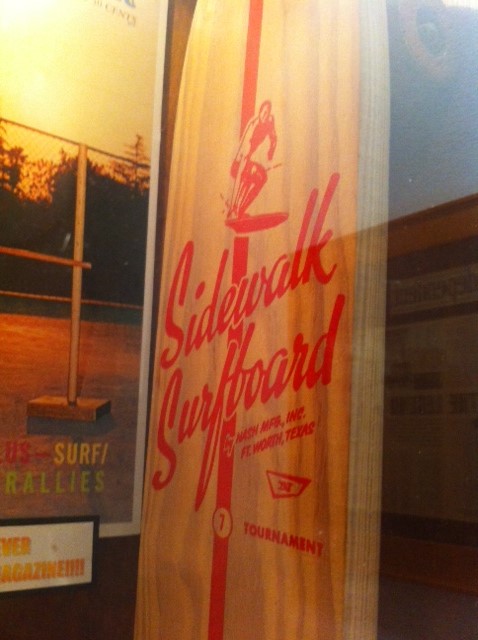

Photo Album – Graphic

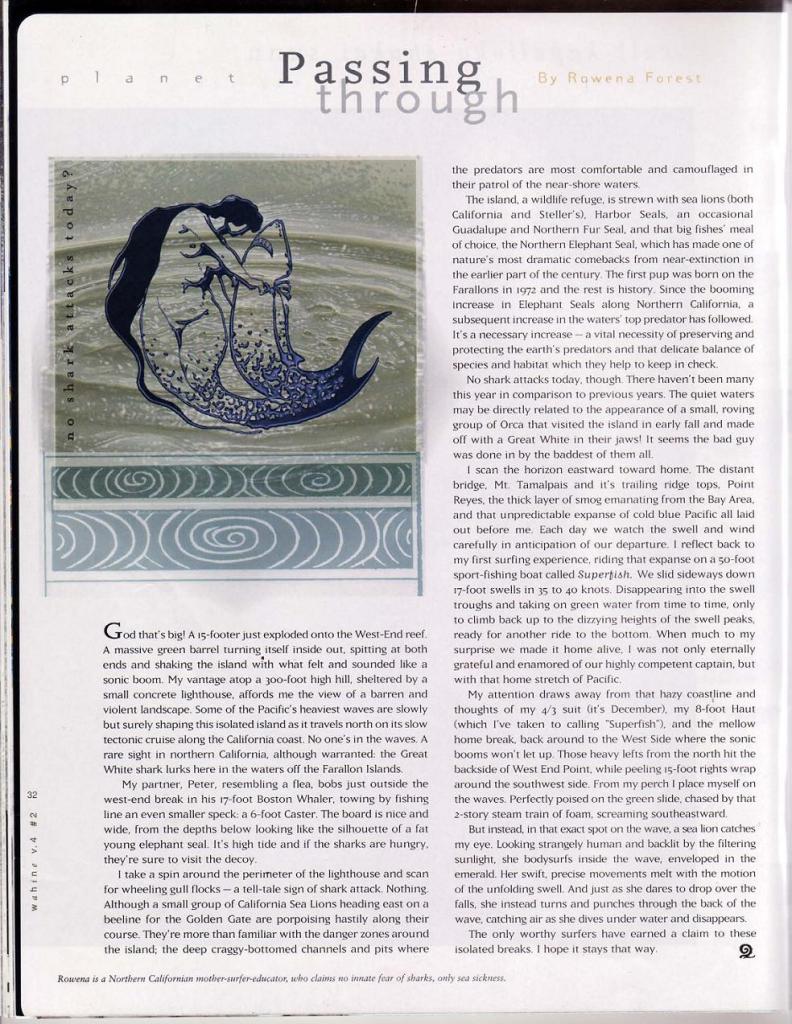

Passing Though – essay in Wahine Magazine

Seasonal Biogeography of the Farallon Islands

This web page was a class assignment, for which I am outlining the seasonal biogeography of the Farallon Islands, based on three major seasonal animal distribution events at the Farallon Islands National Wildlife Refuge

Background:

Farallon Islands National Wildlife Refuge is a small, 7.96 long rocky island chain, which lies 27 miles west of the Golden Gate, at 37° 41’ 56” N, 123° 00’ 12” W

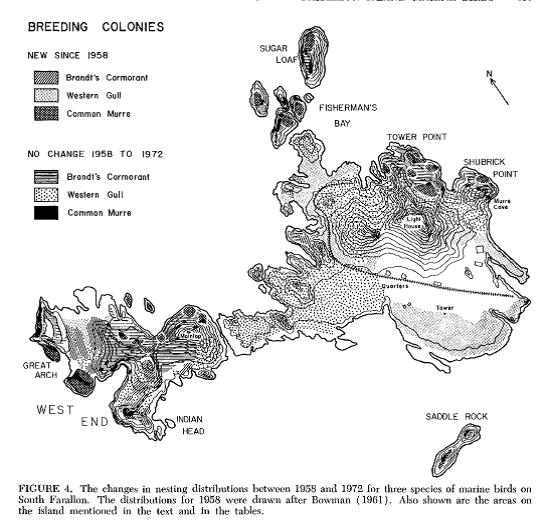

The Farallon Islands host the largest seabird rookery on the west coast of North America, with 12 species of breeding seabirds: Ashy Storm-Petrel, Black Oyster-catcher, Brandt’s Cormorant, Cassin’s Auklet, Common Murre, Double-crested Cormorant, Leach’s Storm-Petrel, Pelagic Cormorant, Pigeon Guillemot, Rhinoceros Auklet, Tufted Puffin, and Western Gull

The Farallones also host large breeding colonies of pinnipeds: Northern Elephant Seal, Northern Fur-Seal, Harbor Seal, California Sea Lion, and Steller’s Sea Lion

Cold, nutrient rich waters of the Gulf of the Farallones, and seasonal upwelling events create an extremely fertile food web and productive ecosystem in the Gulf of the Farallones

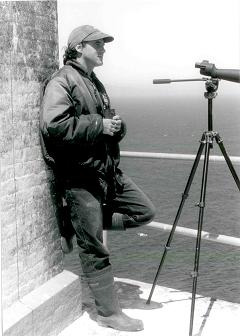

Southeast Farallon Island is the southern-most and largest island of the chain, featuring a U.S. Coast Guard Lighthouse, U.S. Fish and Wildlife infrastructure, and a biological field station run by Point Blue Conservation Science (Formerly Point Reyes Bird Observatory/PRBO). My husband, Peter Bryan Pyle, was the fall biologist for PRBO stationed on the Farallon Islands between 1980 and 2003, with the primary duties of monitoring migrant land birds, monitoring White Sharks, recording all other wildlife activities, collecting of weather and oceanographic data, running the island infrastructure, and working with the US Coast Guard, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Marine Sanctuary program on infrastructure and invasive species projects.

PRBO, has established a 50 year regimen of biological monitoring programs on the Farallon Islands, which follow a distinct seasonal cycle. In the spring through summer intensive study and monitoring of breeding seabirds is conducted; in the fall months monitoring of migrant land birds and White Sharks occurs; and the winter brings the Northern Elephant Seal breeding and pupping monitoring season.

I spent a portion of each fall on the Farallones between 1995 and 2003, and participated in White Shark as well as native and invasive plant monitoring projects. Central to life on the Farallones were long and sometimes harrowing boat trips, harsh weather conditions, rigorous all day field work, nightly communal dinners, followed by a nightly group journal entries of the day’s biological and weather happenings. During fall evenings a fun part of the White Shark monitoring project was to review the raw underwater video footage of White Shark feeding events collected that day. Additionally, I have a very personal connection to the Farallones having grown up watching the pulse of the Farallon lighthouse from my living room window, and had a great-great grandfather who ran his ship aground on Southeast Farallon Island in 1871: one of numerous Gold Rush era shipwrecks on the islands.

Overview of Atmospheric and Marine Conditions at the Gulf of the Farllones:

“Although the Farallones certainly share the weather patterns of the coastal province, there is little doubt that the biogeographic composition and size of the Farallon marine avifauna are influenced by marine rather than terrestrial conditions,” (Seabirds of the Farallon Islands, Ainley et al 1990).

Situated in the Gulf of the Farallones, annual air temperatures at the Farallon Islands mirrors the cold ocean currents surrounding the islands, and only range from approximately 9 to13 degrees C throughout the year (Ainley 1990). Marine advection fog envelopes the islands during much of the summer months, providing summer moisture to terrestrial habitats, and precipitation falls only during the short winter season. The geophysical processes most influential over seasonality and ecology at the Farallon Islands are the presence of the dominant cold California Current, flowing north to south just west of the Farallones, the warmer Davidson counter-current, which occurs in the fall, coastal upwelling processes, El Nino events, and the strengths and positions of the Aleutian Low and North Pacific High pressure systems (Ainley 1990).

As noted in the Seasonality of coastal upwelling off central and northern California: New Insights, Including Temporal and Spatial Variability (Garcia-Reyes, et al 2011), “three seasons are defined to best represent the annual cycle of wind stress along central and northern California. Following the nomenclature used by Largier et al. [1993], but updating the durations, they are defined as: “Storm Season” or winter (December-February), “Upwelling Season” (April-June), and “Relaxation Season” (July-September).”

The strongest northwesterly winds occur from April to June, producing the strongest annual upwelling events, oceanic winds weaken from July through September, and winter brings southerly winds to the Gulf of the Farallones with the passage of cold fronts, (Garcia-Reyes 2011).

Lowest sea surface temperatures at the Gulf of the Farallones are correlated with the strongest northwesterly winds, and warmest sea surface temperatures are correlated with wind relaxation events in the late summer and fall.

Winter on the Farallones:

As winter approaches, the North Pacific High pressure cell move south and east toward the central west coast, northwesterly winds decrease in strength and frequency, and cold fronts, or low pressure systems, move in from the north bringing southerly winds and winter rains to California, (Ainley 1990). With these wind reversals the dominant California Current gives way to the seasonal Davidson Current (or counter current), which now reaches the surface flowing up the coast from south to north.

The winter is marked by the dramatic biogeographic seasonal event of the arrival of the Northern Elephant Seal (Mirounga angustirostris). According to Farallon biologist, Peter Bryan Pyle, the first arrivals of elephant seals to the Farallon breeding colonies are the adult males, which show up in November. After 9 months feeding at sea, they are at their peak weight (up to 5,000 pounds), and begin establishing territories. Adult females arrive to the Farallones mid to late December, at their peak weight and carrying full term pregnancies. These females choose a male’s territory (harem to join), and the first pup is usually born right around Christmas.

By February, the nursing females have used up all their physical resources on nourishing their pups, are mated by the dominant male, and then return to sea to feed, leaving/weaning their pups. When most of the adult females have left the Farallones, the adult males leave by the end of February, and the pups remain alone on islands for another three-four weeks until they become hungry enough to take to the waters and learn to survive in the north Pacific by feeding often at great depths.

Female elephant seals begin breeding around four to five years of age, and dominant (alpha) males are eight to ten years old at first breeding. Fights to the death can occur between bull elephant seals establishing and maintaining their harems, (P. Pyle).

Mature elephant seals also visit the Farallones for a short period from mid-June to mid-July to molt, at which time they are completely docile with each other. Between the summer molt and the winter breeding pupping season, Northern Elephant Seals are feeding in the Gulf of Alaska. This twice yearly round trip constitutes the longest known annual migration for any mammal species in the world (Point Blue Conservation Science – Los Farallones blog).

Once exterminated from the Farallon Islands by 19th century American and Russian sealers, the Northern Elephant Seal returned to the Farallon Islands to pup in 1972. Since that time, biologists with the Point Reyes Bird Observatory (PRBO – recently renamed Point Blue) have monitored the breeding colony. As described by Derek Lee in, Population Size and reproductive Success of Northern Elephant Seals on The South Faralon Islands, 2005-2006, “Since 1972 nearly all weaned pups and several immature animals were flipper-tagged every year. PRBO biologists identified returning females by flipper tags, distinguishing marks such as scars, or by dye marks placed on animals during post-breeding molt. After recording tag numbers, PRBO biologists used hair dye (Clairol, Stamford, Connecticut) to mark females temporarily so they could observe animals from a distance. Pups usually were marked with dye 1 or 2 days after birth. PRBO biologists checked mothers and pups daily, weather permitting, to determine parturition and breeding success. All work was carried out according to guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists.”

Spring-Summer on the Farallon Islands:

In the spring and summer, from about April to June, the northwest winds reach their peak strength, increasing in speed and duration of wind events. The strong northwest winds fuel the process of upwelling along the central California coast, and cause sea surface temperatures at the Farallones to reach annual lows (Ainley 1990). “The beginning of the upwelling season, known as the spring transition, is marked by an increase in the magnitude and persistence of equatorward wind stress, and it is an important factor for the ecosystem, as it marks an increased availability of nutrients and thus the start of the season of high primary productivity,” (Garcia-Reyes et al, 2011).

This season of high marine primary productivity marks the seabird nesting season on the Farallon Islands. The immense numbers of seabirds and size of the breeding colonies on the Farallones is staggering. Once depleted by hunting and relentless egg collection, the seabird populations on the Farallones have still not recovered to their historic numbers, but remain the largest rookery off the west coast of North America. “On this group of rocky islands, situated just 43 km out to sea from San Francisco, is not just the largest concentration of breeding marine birds in the United States outside of Alaska and Hawaii, but it is a diverse avifauna as well.. The overall result of the many reports is a documentation of an avian community over a time span probably unsurpassed in the Western Hemisphere,” (Ainley 1990).

The twelve species of seabirds which nest on the Farallones are the Ashy Storm-Petrel, Black Oyster-catcher, Brandts Cormorant, Cassins Auklet, Common Murre, Double-crested Cormorant, Leach’s Storm-Petrel, Pelagic Cormorant, Pigeon Guillemot, Rhinoceros Auklet, Tufted Puffin, and Western Gull.

These twelve species have been continuously monitored on Southeast Farallon Island by Point Blue (formerly Point Reyes Bird Observatory/PRBO) since 1971, for population size and reproductive success, (Warzybok , 2014). Seabird monitoring data at the Farallones is collected on survival, phenology (timing of breeding), chick growth, environmental conditions, and prey use (diet composition). “These long-term data give us a unique ability to examine trends over multiple time scales and look at variability in the context of long-term patterns and trends,” (Warzybok 2014).

Fall on the Farallon Islands:

In the fall months, three major oceanographic processes affect the marine environment of the Gulf of the Farallones (Pyle et al, 1996): the weakened California Current, the strengthening Davidson counter-current, and weakening coastal upwelling. As defined by Garcia-Reyes et al, 2011, early fall is characterized as the “relaxation season” for northwesterly wind stress (July-September), and transitions to a September through November period of calm winds, wind reversals, and warming sea surface temperatures throughout the fall months.

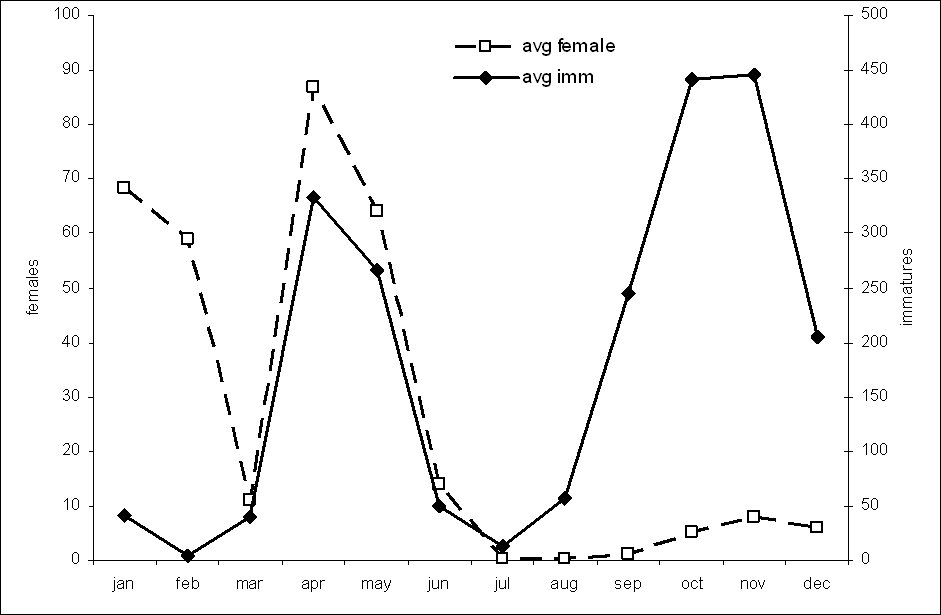

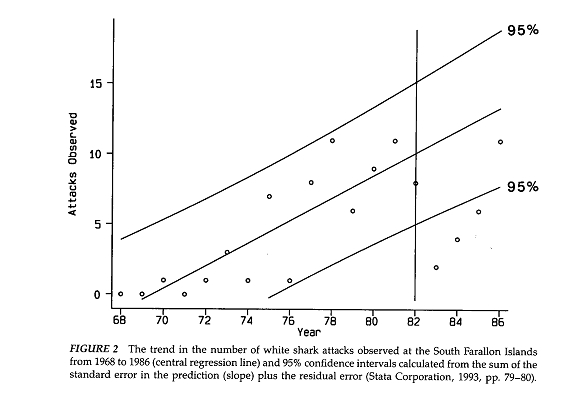

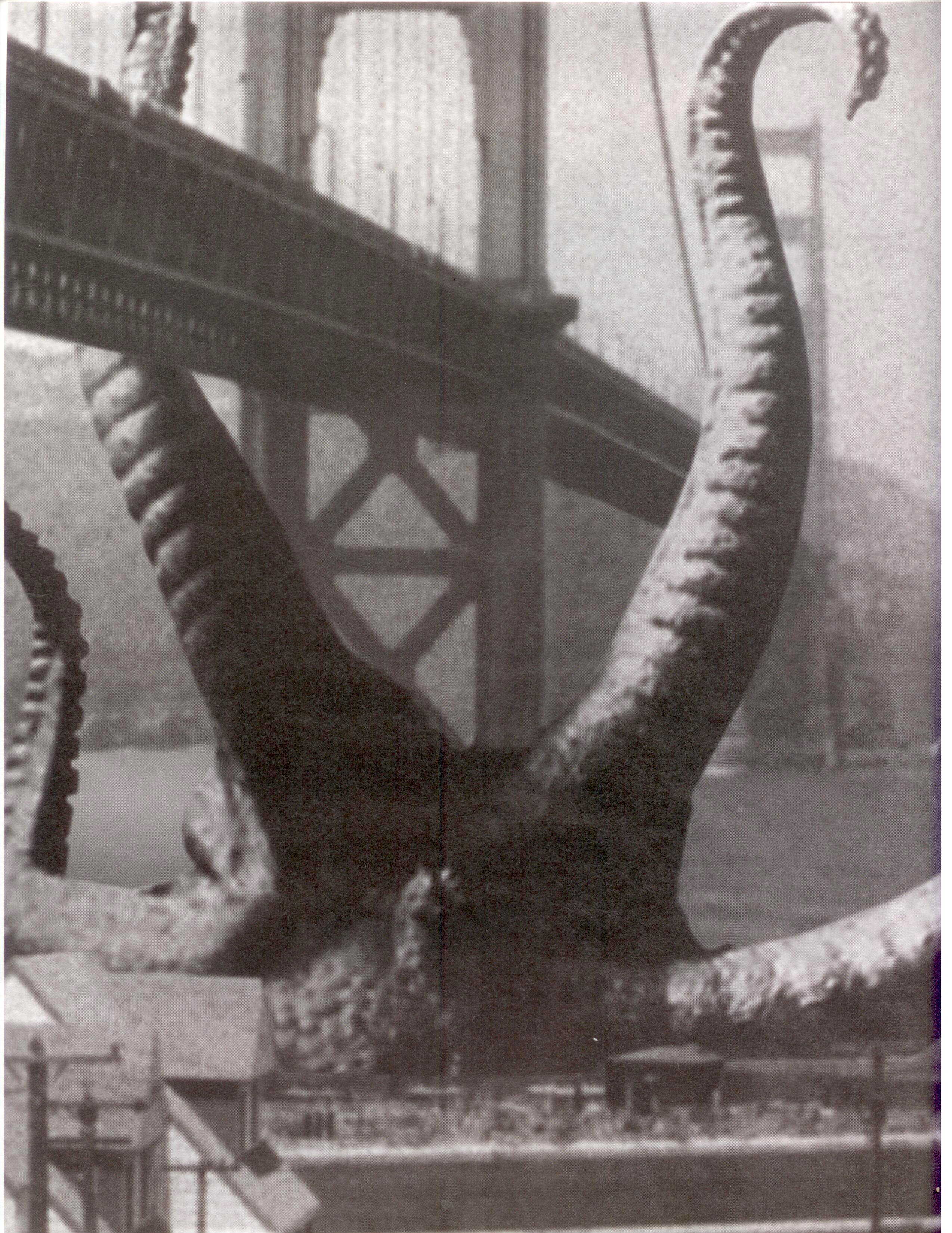

A fascinating seasonal biogeographic occurrence at the Farallon Islands is the migratory return of the Great White Shark surrounding waters in the fall months of September through November. This seasonality is attributed to prey availability of immature Northern Elephant Seals and other pinnipeds in the fall months (Pyle et al 2003).

Predation by White Sharks on pinnipeds had been observed by Farallon biologists on island since the early 1970’s, and a methodological White Shark monitoring project was launched in 1987. “From 1987-2000 during daily observation in autumn (1 September to 30 November), we identified and documented individual white sharks using size and unique markings such as scars, mutilated fins, natural pigmentation patterns, and the distribution of notches on the trailing edge of the dorsal fin. From 1987-1992 sharks were documented with still photographs and shore-based video recorders. By 1993 we discovered that white sharks investigated small vessels or decoys particularly during and up to two hours subsequent to feeding events on pinnipeds. This behavior allowed us to employ underwater video recorders mounted on poles to document individual sharks and confim sex,” (Pyle et al, 2003) .

Based on this long term study, biologists found that White Shark attack (predation events) frequency increased with date, number of immature elephant seals present, higher tide, lower water clarity, bigger ocean swell, strong ocean upwelling the day previous to the attack, decreased wind speed, increased sea surface temperature, and decreased moonlight (new moon portion of the lunar cycle), (Pyle et al, 1996). Seasonal populations of White Sharks at the Farallones were estimated at 10-14 individuals at a minimum (Anderson et al 1996) with a possibility of 40 individuals per season at the highest (P. Pyle 2017). “Most White Sharks at the Farallones were found to be transient visitors, with a few short-term residents,” (Anderson 1996).

Other curious and significant findings include the pattern of individual sharks feeding at the same locations on similar dates on successive years (Anderson et al, 1996), leading scientists to surmise that sharks regulate the timing of their extensive, Pacific-wide movements far more precisely than previously perceived. Also discovered through long term monitoring, are temporal sex-specific occurrence patterns among adult white sharks at Southeast Farallon Island, with adult males occurring every year, and females occurring every other year at most. “This sex specific occurrence pattern implies a 2-year reproductive cycle, resulting in a lower reproductive potential than previously thought, which has important implications for the conservation of this species. These results also suggest that female white sharks may travel significant distances in the North Pacific Ocean during a biennial reproductive cycle to give birth, whereas copulation may occur closer to northern CA, allowing males to return annually to SEFI,” (Pyle et al 2003).

References:

Ainley, David, Robert Boekelheide. Seabirds of the Farallon Islands. Palo Alto: Stanford

University Press, 1990.

Ainley, David, T. James Lewis. “The History of the Farallon Island Marine Bird Populations,

1854-1972.” The Condor 76, (1974): 432-446.

Ainley, David, Peter Klimley. Great White Sharks: The Biology of Carcharodon carcharias. San

Diego: Academic Press, 1996.

Anderson, Scot, Taylor Chapple, Salvador Jorgensen, Peter Klimley, Barbara Block. “Long-term

individual identification and site fidelity of White Sarks, Carcharadon carcharias, in

California using dorsal fins.” Marine Biology 158, (2011): 1233-1237.

García-Reyes, M., and J. L. Largier. “Seasonality of coastal upwelling off central and northern

California: New insights, including temporal and spatial variability.” American

Geophysical Union 117, (2012): 1-17.

Karl, Herman, John Chin, Edward Ueber, Peter Stauffer, James Hendley. “Environmental Issues

in the Gulf of the Farallones.” United States Geologic Survey, (2001): 1-78.

Klimley, Peter, Scot Anderson, P. Bryan Pyle, RP Henderson. “Spatiotemporal Patterns of White

Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) Predation at the SouthFarallon Islands, California.”

American Socieity of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists 1992, no. 3 (1992): 680-690.

Lee, Derek. “Population Size and Reproductive Success of Northern Elephant Seals on the South

Farallon Islands 2005-2006.” Journal of Mammalogy 92, no. 3 (2011): 517–526.

Pyle, P. Bryan, Scot Anderson. “A temporal sex specific occurrence pattern among white sharks

at the south farllon islands, CA.” California Fish and Game publication 89, no. 2 (2003): 96-101.

Pyle, P. Bryan, Scot Anderson. “A temporal sex specific occurrence pattern among white sharks

at the south farllon islands, CA.” California Fish and Game publication 89, no. 2 (2003): 96-101.

Pyle, P. Bryan, Peter Klimley, Scot Anderson, Philip Henderson. “Environmental factors

affecting the occurrence and behavior of white sharks at the Farallon Islands, California.”

Academic Press, (1996): 281-291.

Warzybok, Peter, R.W. Berger, R. W. Bradley. “Status of Seabirds on Southeast Farallon Island

During the 2014 Breeding Season.” Unpublished report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service,(2014):1-13.

Ancestral Journey to the Farallon Islands

In the darker hours of night, the tiny pulsing of the distant Farallon Island lighthouse could be seen from my childhood living room windows. I sat backwards on our sofa, facing out to sea with chin resting on my folded arms, leaning forward against the couch back, face close to the cold window, gazing into the black and counting the seconds between the flashes. What we knew about the islands as kids, was only that there were sharks there… and lots of seals. And if you took a boat to the Farallones you would see a shark eating a seal. We also knew that the island was impossibly far away, and only bird watchers went there for some reason. What I didn’t know about the Farallones was that one day I would fall in love with a resident researcher, that I would have the privilege of escaping to the island from the difficulties of my adult life for a week at a time, and that my great, great grandfather – a Danish sailor – once collided with those islands, a shipwreck that would lead to the settlement of he and his family in San Francisco – thus allowing me to rest my chin on the couch back, gazing out the window 100 years later.

The ocean is one of those things in life where the more experience you have with it, and the more familiar you get with it, the more scared, humbled, and cautious you become in its presence. There’s no other way to learn this from the ocean, but the hard way. And if you don’t learn quick you might end up dead, or wanting to move east. The boat trips I took to the Farallon Islands taught me this. Quickly. They are fun stories to tell now, but at the time they were uncomfortable and anxious experiences at best. The only reason I kept coming back for more was because I was in love, and it was the only way to see my boyfriend… and the only way to escape. The Farallones have provided an escape for small waves of adventurous people for over 100 years. Some appreciated the solitude and extremely rugged environment, some profited from the loneliness of the islands, and others hated it. I’m not sure what my great, great grandfather Hans “Henry” Emil felt about the place, but I’m glad he saw it, and I’m glad he survived.

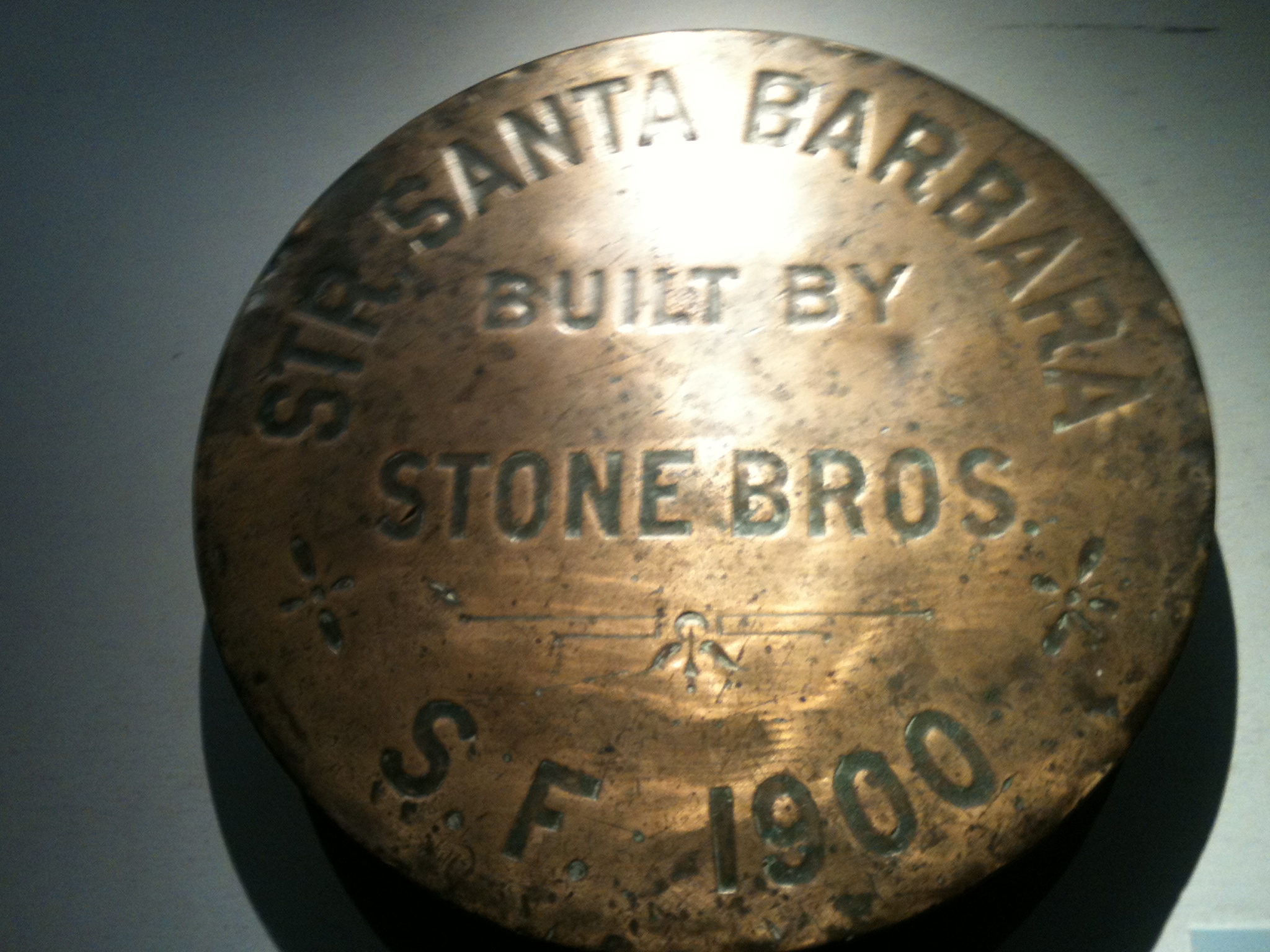

A compromise I reached with the sea, in exchange for regularly tempting its fate in crossing the extremely unpredictable and rough stretch of water between the San Francisco Bay Area and the Farallon Islands, was to pick my days and pick my vessel. The boat of choice was the Superfish, skippered by Mick Menigoz. A large sport boat with strong motors and a level-headed captain. This made for a quick passage generally, but even on the Superfish we had our days. (see my article in Wahine Magazine, “Passing Through”)

Other challenging trips to the Farallones for me included a ride out on an open 13-foot Boston Whaler with no seats in 15-foot seas, which we met head-on as soon as we made that westward turn from the Bay and headed out under the Golden Gate Bridge. The only thing that saved me from extreme fright on that trip was extreme sea sickness. Once outside the Gate we found that our marine radio didn’t work, leaving us with no method of communications in case of an emergency, or with the island, which was somewhere out beyond the breaking waves in front of us. For four hours we caught air off each swell, only to find the landing boom at the Farallones (necessary for lifting personnel onto the island) had broken that morning and was barely patched together with just enough spit to lift me out of the water and up to salvation on dry land. The two guys that took me out in that tiny, open boat had to turn right around and do it all again for at least a few more hours in rising swells, in order to get back home before dark. Somehow they made it, and it took me a couple of days on the couch to completely recover from the ordeal.

There were other hairy trips: one with an aged, one-eyed skipper and his yacht club, wine-glass-clinking friends. Errors in judgment took us on a “tour” of the island, circling around the most treacherous areas of the Farallones, heading into the wrong end of terrible sea conditions – waves cresting at the side of the cruiser, but somehow never quite breaking over us. A gray whale was nearly struck by the boat on that round-island tour. No one seemed to notice anything except me, and all I could eventually do was sit down and hold on in the lowest spot mid-deck, as the biologists on the island attempted frantically to hail the captain on the radio and tell him to turn back – to no avail.

The stories go on, and mine are by no means the worst. I can’t imagine what my great, great grandfather saw in his many schooner trips around the world – through many seas and seasons. I can’t imagine the emotions one goes through when your ship runs aground, let alone during a devastating shipwreck. I try not to think about it. My curiosity has led me, however, to try to find out the details of this boat he was on, and its encounter with the island. Our family stories of the wreck were by now at least fifth-hand/fifth-generation accounts, with no hard facts. Maybe it never happened, but it was a good story worth investigating.

I began my research in earnest online. I only knew the year, but not the name of the boat, or what position Henry held on-board, other than that he was one of the top mates or steersmen. It would have been about 1871, and a large merchant ship heading-in from the south I assumed. Online I found the California State Lands Commission Shipwreck Database, and a good spreadsheet of all shipwrecks that have occurred near the Golden Gate posted by the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. All the dates so far were a decade too early or a decade too late. Ships with names like the Bessie Everding, the Beeswing, the Franconia, Lucas, and Noonday were listed as: “foundered”, “stranded”, “lost” or “all hands saved”. Most were wrecked along the north coast’s mammoth rocky reefs and submerged sand bars. A few had met their fate at the Farallon Islands. Nothing matched perfectly. But one, the Annie Sise, was listed as running aground in Marin in 1871– with no other details.

I dove into our copy of The Farallon Islands: Sentinels of the Golden Gate by Peter White, and online I encountered a handful of other intriguing titles, including Shipwrecks at the Golden Gate. From historic ecology research projects I had conducted in the past, I knew the San Francisco Public Library’s main branch had a wonderful history room, so I got off the computer and headed down to The City to do some real digging. The main branch is palatial, and I dropped off my mom in the library’s second floor at the poetry section, and headed on upstairs to the archives. Investigating several different resource angles that day, I was able to determine that the Annie Sise had in fact run aground on the Farallones! It was 1871, and all hands were saved. Also, it was the only wreck on the Farallon Islands that year, so it was a good bet that was his ship. I then spent hours reviewing microfilm of the four newspapers printed in San Francisco during 1871, in hopes of uncovering a record of the incident: The Daily Alta California, The San Francisco Chronicle, The San Francisco Daily Morning Call, and The Daily Evening Bulletin. Finally, in the Daily Alta California I found the following:

September 18th, 1871,

“The Wreck of the Annie Sise”

Captain Howland of the ship Governor Morton, upon his arrival yesterday, reported a ship ashore on the South Farallone Islands. Upon the United States Steamer Wayonda proceeding to the islands, it proved to be the ship Annie Sise, previously reported as having been lost on Point Reyes. The commander of the Wayonda presented the following report:

“Parties on the Farallone Islands gave the following account of the wreck; They saw the ship Annie Sise ashore on the west end reef, South Farallone Islands, on Friday at 6:10pm. She had all sails set, and anchors hanging by shank painters. The ship did not go to pieces until sometime during the night of the 16th. The report having found the ships log and chronometer boxes, but the chronometers were gone. The cabin was well cleared out. Two boats were lashed on deck and two boats gone.”

It was reported in the Daily Alta California on September 17th, regarding the same wreck:

“All hands left the ship in two boats, and reached the bar at 2:00 a.m. yesterday, where they fell in with the schooner John and Samuel, hence for Point New Year, whose master, Captain Borrill, kindly took the crew on board and landed all hands safely in the City, where they arrived at nine o’clock in the morning…”

It turns out that this trip of the merchant ship, Annie Sise, originated in New York, and she sailed around the globe reaching California via Australia along her trade route. I have researched several other resources including the Port of San Francisco records and archives, and the National Archives in hopes of finding the ships log or crew list from this voyage. All of the Port of San Francisco’s passenger-arrival records from 1850 – 1907 were lost in a fire at the Angel Island’s records facility in 1940. If I want to find a crew list for the Annie Sise it will need to turn up some other way, most likely from out of state, and most likely by luck or by chance.. but I haven’t given up. For now, I’m placing my bets Hans Emil was aboard that ship when she ran aground on the Farallones 139 years ago.

Update to Ancestral Journey to the Farallon Islands

As reported previously in Coastal Roots, in Ancestral Journey to the Farallon Islands, we have been searching for the name of the vessel and confirmation of my great-great grandfather, Hans Heiner’s name as crew, and possibly mate, aboard a schooner wrecking on the Farallon Islands, CA in the 1870’s. I had narrowed down the most likely boat to the Annie Sise, which shipwrecked on the Farallon Islands, CA in 1871 – All hands saved and rowing in the life boats toward San Francisco, to be picked up by another ship and brought to port in SF safely. But despite months of research of crew list and ship log journals, I could not find a complete list of names. We now have come across the desired evidence, and can close the chapter on this search: According to the shipping reports in the Melbourne Argus, May, 1871, “Hans Hyner” was Chief Officer of the Annie Sise, and brought her in to port there after the captain had died at sea – just months before wrecking in California.

Photo Album – Historic Marine Labs

Hopkins Marine Station, Pacific Grove

Bolinas Marine Station/College of Marin Marine Biology Lab

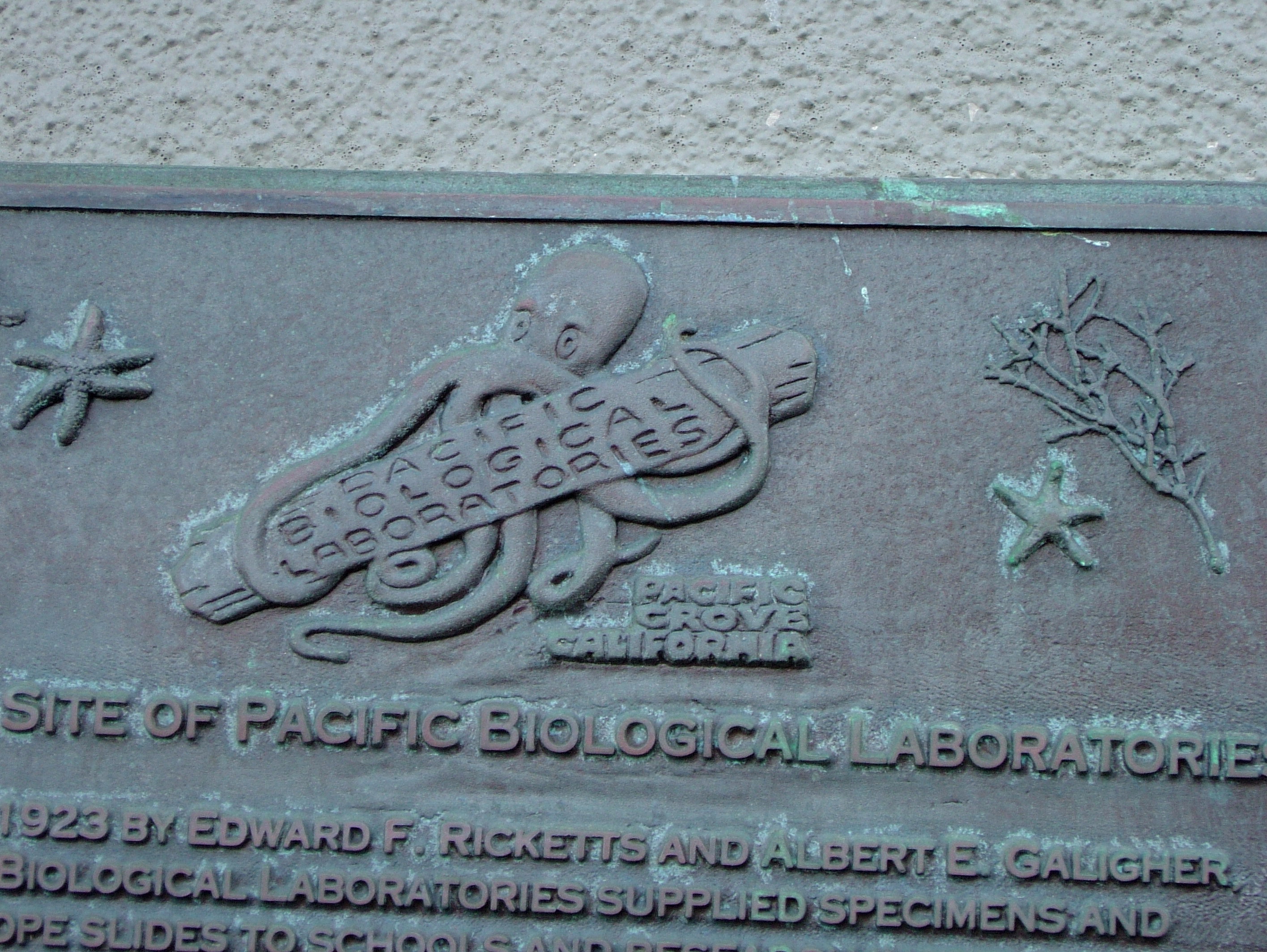

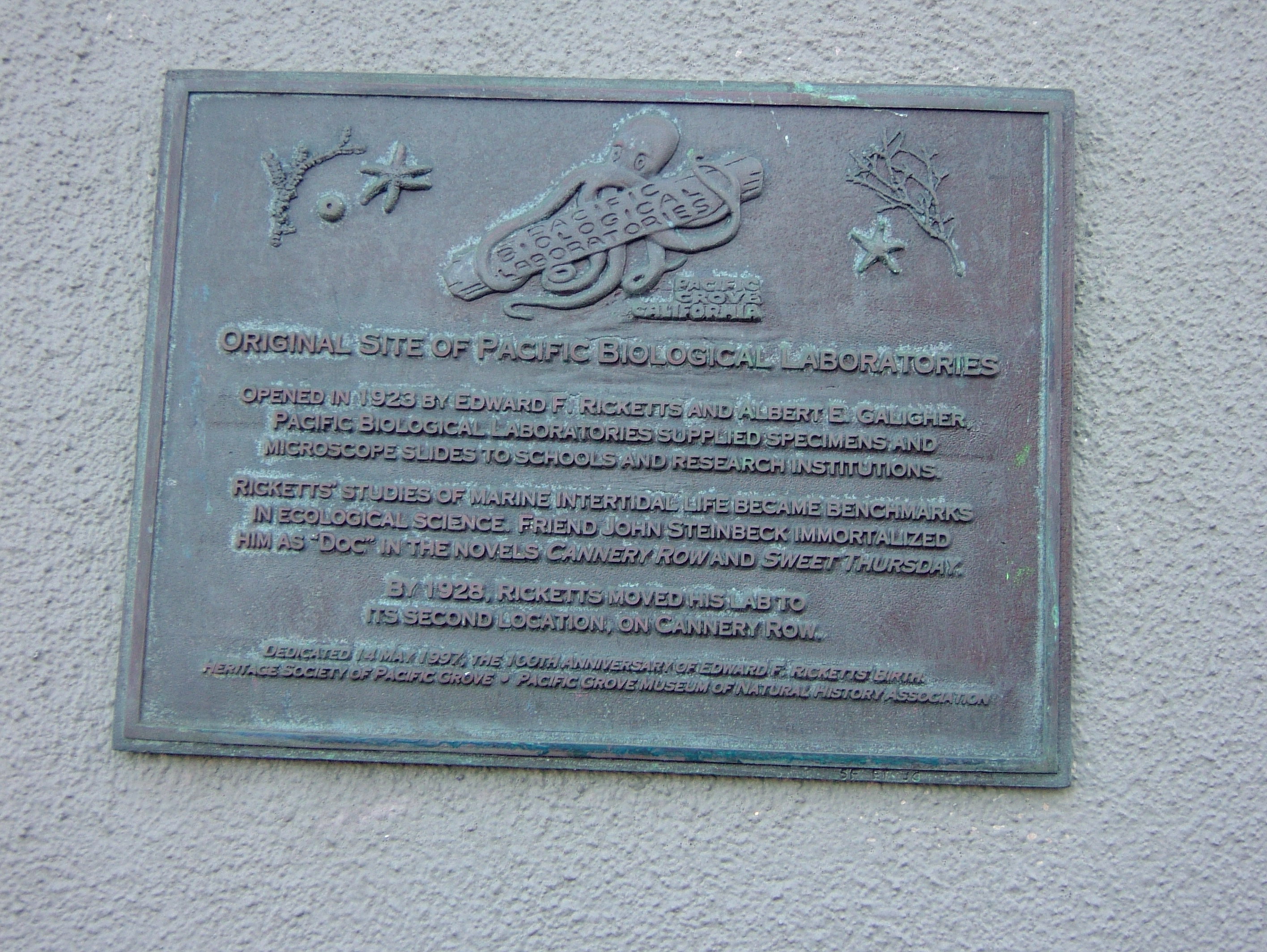

Pacific Biological Laboratories, Monterey

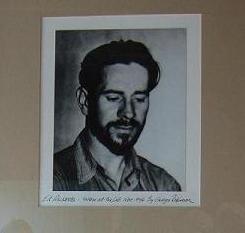

Ed Ricketts’ Pacific Biological Laboratories

I thought I’d take a simple little trip to Monterey and write a neat little piece on the historic Pacific Biological Laboratories of Ed Ricketts – the place that inspired the creation of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, served as the center piece in John Steinbeck’s classic novel, Cannery Row, and has inspired multiple generations of marine biology lovers and professionals since the 1920’s. Days later I was still in a bittersweet fog.. like I had been thrown back in time myself. The era in which Ed Ricketts lived, where he lived, and how he lived his life holds a significant mystique that cannot be duplicated. What a time it must have been.

I didn’t expect to find the site of Pacific Biological Laboratories where it is: Front and center on the Cannery Row stage – squished between two massive ex-canneries (one now a luxury hotel) right at the water’s edge and practically adjoining the Monterey Bay Aquarium. I thought I’d find the lab up the hill in the old neighborhoods for some reason… I must have walked by it 10 times over the years in my visits to Monterey for meetings or to go to the aquarium. I parked the truck in the shade for my dog, fed the meter a zillion quarters, and jogged down the ragged east end of Cannery Row toward my destination. I wanted to make sure to catch the next hourly tour of the lab at noon. Open only once or twice a year to the public, in cooperation with the Cannery Row Foundation, Pacific Biological Laboratories is a hot commodity not easily acquired. I’ve been trying to find a way to see it for years, and now I finally will.

I swerve through throngs of tourists meandering Cannery Row on a sunny and crisp Saturday morning. There it is up ahead, in all its dwarfed and rustic beauty. I slow my approach to read a handwritten sign stapled below the stairwell advertising the hourly tours. No one is around so I better hurry in. I start to jog up the creaky wooden stairs toward the old front door, and it hits me. It feels like I’m walking on an exhibit, a fragile antique preserved in time. It shocks me that I’m allowed to do this, and I feel excited and lucky – like I should sneak so I don’t get kicked out. Must have been the sound and feel of that creaky step under my foot, and all at once it feels familiar and like I’m 60 years too late.

For a moment the street is quiet behind me – no one is around. No tourists on the wide sidewalk below, no cars crawling by looking for aquarium parking. The multi-paned windows of Ed Ricketts’ front room are above and to the left of me, weathered and set into the even more weathered dark wooden framing. The call of Western gulls echoes off the waterfront buildings around me. Behind me are the empty lots of weeds and cannery debris, the dirt roads, tree frogs singing in the road puddles, the sandy hills dotted with cabins and shanties, the black cypress and pine covered mountains as backdrop. The door is a few steps above me. There’s motion from the other side of the windows, and the knob begins to turn. Will he step out on to the tiny landing and invite me in? I see Ed clearly looking down at me.

Then the street is back. Not the canneries anymore but hotels, boutiques, and restaurants. There are no weedy lots or dirt roads. I knock tentatively on the door, and am greeted by a small group of friendly, mostly seated older folks who invite me in to sit and have a drink before the next tour gets going.

Most people interested in this stuff know that Ed Ricketts was far more than a biologist. He was a philosopher, a lover of music and art, a voracious reader, an explorer, quiet, kindly and focused, a legendary bohemian, caring friend to many, and frequent party host. His home/lab was a gathering place for like-minded friends and strangers. Joseph Campbell and John Steinbeck kept his company, as well as the local kids, drifters, fishermen, biologists and lady friends.

Ed had a succession of three marine biology labs in the Monterey area. The first opened in 1923 in Pacific Grove, then two at the same location on Cannery Row. The first at the Cannery Row location burnt down in 1936, and Ed never fully recovered financially from the great loss of personal and professional items. He escaped the blaze (which started in and consumed the canneries around him) with his typewriter, a portrait of himself, his pants, and his car. All else lost: art, music, household items, equipment, his specimens which were his livelihood, and his extensive and beloved library.

What was saved from the fire, however, was the manuscript for Between Pacific Tides – which would become the timeless intertidal bible of the west coast, encapsulating Ed’s life work of shoreline exploration along the west coast. The manuscript was saved because it lingered at Stanford University Press as they dragged their heels in publishing a work by an author who had left college early and had no degree to show for his name. But eventually publish it they did, and word has it that it is still the most popular marine textbook produced by Stanford. A true classic.

Ed preserved marine specimens, as well as cat skeletons and frogs for high school and college biology classroom use in schools across the Country. This is how he squeaked out a living through the depression and beyond. Ed’s non-stop collecting and cataloguing of intertidal marine life in California extended to collecting trips in Alaska and Mexico as well. He endeavored to complete catalogues of the intertidal ecosystems of much of the west coast of North America. With the completion of such a body of work, Ed Ricketts would have been known as the undisputed pioneer of western marine biology he so deserved. This work was cut short by his death in 1948 when his car was struck by a train as he crossed the tracks near his home in Monterey.

Although a great help in making his work known to popular audiences, the likeness of Ed Ricketts as “Doc” in Cannery Row was only a “thin veneer of the complicated man Ed Ricketts was”, as one of the knowledgeable and engaging docents on the lab tour put it. Cannery Row, written as a tribute to Ed Ricketts whom Steinbeck held in high reverence, has, as it turned out, overshadowed Ed’s considerable scientific accomplishments.

I entered the lab and began to absorb the surroundings. In honor of Ed I took up the offer for a drink, and engaged in red wine for breakfast. I looked around and chatted with the group of colorful local authors, historians and archivists who have made it their passion to research and tell the tale of Ed Ricketts and the real Cannery Row to lucky interested parties such as myself. The place is dark but inviting, and felt somewhat like a small drafty barn with windows. It is barren of hominess and one can see right through the lab from the front sunlit living room strait out the back to Monterey Bay. None of Ed’s furnishings remain, and since his passing the walls dividing the tiny rooms he used in his office/living quarters have been removed to create two main common rooms upstairs.

There have been a few owners of the building since Ed died 1948, but all have cared for the lab in his honor, and preserved it as best they could. Since the 1950’s the lab has been owned by a group of businessmen and artists who formed a “gentlemen’s club”, which meets regularly at the site mostly for social events. What remains in the building are artifacts of this club: books, an old record player, a bar built in the back room, a piano, artwork, and some reproductions of portraits of Ed Ricketts on the walls. One notable artifact of the men’s club is a collage in the front room decorating the entire western wall comprised of photos of jazz musicians, sexy actresses of the day such as Sophia Loren, a young Fidel Castro, local characters of Monterey and the men’s club, and prints of modern art.

Beneath this wall once sat Ed Ricketts bed, and his library shelves. The patched hole low in the wall where Ed’s potbelly woodstove once stood close to his bed, remains. On this western wall Ed had hung a paper timeline on which he invited anyone to list historic facts of significance in the arts, sciences, philosophy, and civilization throughout time which they had learned. No one knows what became of that paper timeline or much else of Ed’s belongings after he died. Understandably, friends and family took bits and pieces of Ed to remember him by until nothing was left here – Only the skeleton of his concrete specimen tank system out back, some extra large ceramic mason jars in the lab below, and the floors we stood on. If those floors could talk.

Some of Ed’s marine specimens are reported to be at various museums and academic institutions around the San Francisco Bay Area. The Gentlemen’s club has deeded the building to the City of Monterey, and when the last of the few remaining members of the club move-on, the city will take up full ownership of this great place. It remains to be seen what the plan is for the building: One hope is for a renovation to restore the lab as it once was when Ed Ricketts worked and lived there – a replica open to the public to preserve his memory and legacy.

I easily return there to the bustling lab of the 20’s, 30’s, and 40’s, and the streets and the life of Monterey’s working waterfront. Watching Ed work and talk and host. Similarities in my own life bring me there. I grew up in a place, time, and community like Cannery Row.. there was even an old marine lab that inspired a community of kids, students, and philosophers. But nothing really compares to Ricketts’ lab and Cannery Row in old Monterey.

Recommended Reading:

Renaissance Man of Cannery Row – The Life and Letters of Edward F. Ricketts, edited by Katharine Rodger

Between Pacific Tides – Edward F. Ricketts and Jack Calvin

Beyond the Outer Shores – Eric Enno Tamm

The Log from the Sea of Cortez – John Steinbeck

Photo Album – Marine Life

wordpress template won’t let me put captions on this gallery.. A bunch of random marine life mostly from central CA coast, Gulf of the Farallones, Bolinas Lagoon, etc. Including a scooting Red octopus, new moon Grunion run on Bolinas Beach, Guadalupe fur seal, Night heron, etc

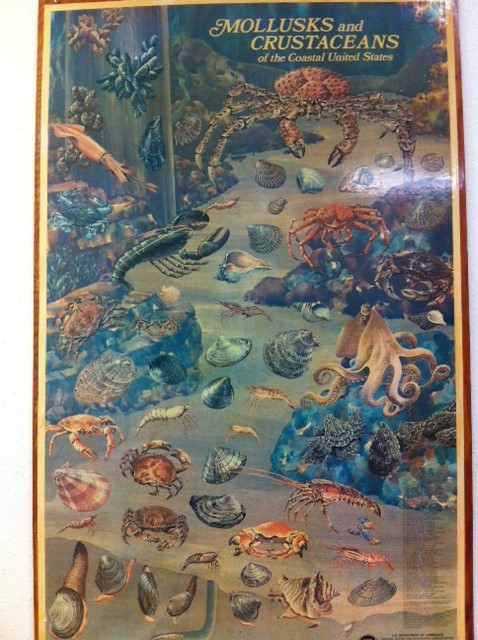

Bolinas Marine Lab

To those with the ocean bug, marine biology labs are more than just classrooms and workshops – they are treasure chests, enticing in their mystique, exciting and abounding with odd possibilities. The sounds of the pumps and rushing water, the humming tanks, the elaborate work stations and sinks, the posters on the walls of exaggerated and colorful marine life you could only imagine seeing in the flesh, the cool air, salty smells and wet floors, the artifacts of the beach rack and old seaside dump sites decorating the window sills and high shelves. There are many fine marine labs along the California coast, several affiliated with prestigious academic institutions such as the UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab, The Romberg Tiburon Center affiliated with San Francisco State University, and the UC Santa Cruz Long Marine Lab. Here I will be focusing on two smaller labs – both of extreme historic significance, unique character and mystique, and both served to influence and change the lives of many kids, students, and visitors in similar magic ways.

When I was a kid growing up in Bolinas in the 1970’s there was a marine lab on the waterfront filled with all of the above. A large antique and official looking building – something unusual in this small coastal agrarian and hippy town – The College of Marin’s Bolinas Marine Lab lured us in as kids time and again. There always seemed to be someone knowledgeable and cool around the lab to let us in, show us the bubbling tanks and specimen jars, and allow us to generally run around and explore the lab and yard. The waters of the Bolinas Lagoon lapped under the dock across the street, kingfishers cried from the overhanging oak trees on the close hill above and behind the buildings, someone would skate by to discuss a fossil found on the beach, or joke about the surf on their way to the neighboring surf shop to repair a dinged board. We’d run in with fossil sand dollars, sea glass, “sightings” of imagined biota in the wide rushing lagoon channel or off the beach down the street. I thought every kid had a marine lab in their town to run around in.. it was natural and something we always looked forward to. Well, as it turns out this was not the norm for childhood experiences, and we were lucky – as have been the hundreds of college students, staff and visitors to this great facility.

The buildings that house the Bolinas Marine Lab and offices were built alongside a sheltered harbor near the mouth of the Bolinas Lagoon in 1914, as the Bolinas Bay Lifeboat Station. The lifeboat men of that era rank near the top for holding one of the all-time most dangerous marine jobs: Assigned with rowing large open sea-worthy skiffs out to particularly treacherous locations known for shipwrecks, in order to save as many lives possible amidst the chaos and dangers of sinking or grounded vessels. Duxbury reef was one of these sites, with a long list of lost ships and passengers to its name – including its namesake. The Lifeboat Station had two lookout towers on the neighboring hills in town, where they monitored for ship groundings on the mammoth Duxbury Reef, with its most prominent reef feature running north/south approximately, and over a mile out into the ocean from Bolinas Point.

The Lifesaving Service morphed into the U.S. Coast Guard over time, and when the Coast Guard left the town of Bolinas in the 1950’s, the old lifeboat station was turned over to the Marin Junior College in an inter-governmental transfer. The college soon converted it to a marine biology lab and education center, and it thrived as such for over thirty years. Recently viewed as expensive to maintain and a liability to public safety by the college, the historic buildings have fallen into disrepair and neglect.

There are only a handful of the historic lifesaving stations left in the U.S., and the Bolinas facility is one of them. Ralph Shanks, Maritime Historian, identifies the Bolinas Marine Lab facilities as “One of the most historically significant maritime buildings on the American coast”. The significance of these buildings is such that they easily could qualify for national or state historic site status.

In the past this facility had so touched the lives of several College of Marin staff, that some personally took it upon themselves to keep the lab and facilities up and running for students – inspiring a new generation of marine biologists and conservationists. The fight to maintain and use the facilities hadbecome too great for any individual or handful of staff to keep up with alone. Under Measure C – the College of Marin Facilities and Modernization Program, consultants were hired to assess the safety of the lab and buildings and the cost of modernization. The findings and assessment were daunting, if overblown. Where as real concerns for structural integrity and environmental hazards in such old building are warranted, these could be more realistically remedied than the natural disaster issues sited, such as possible un-detected earthquake fault lines under the buildings, and fears of loss and damage in the event of a tsunami. Many people including College of Marin staff, students past and present, and community members rallied in the face of the real threat that College of Marin would sell the historic buildings to private interests. These concerned groups succeeded in saving the lab as an educational institution for future generations of marine students. Unfortunately the buildings were demolished in 2021 due to overwhelming structural issues, but a new lab will be built in its place.

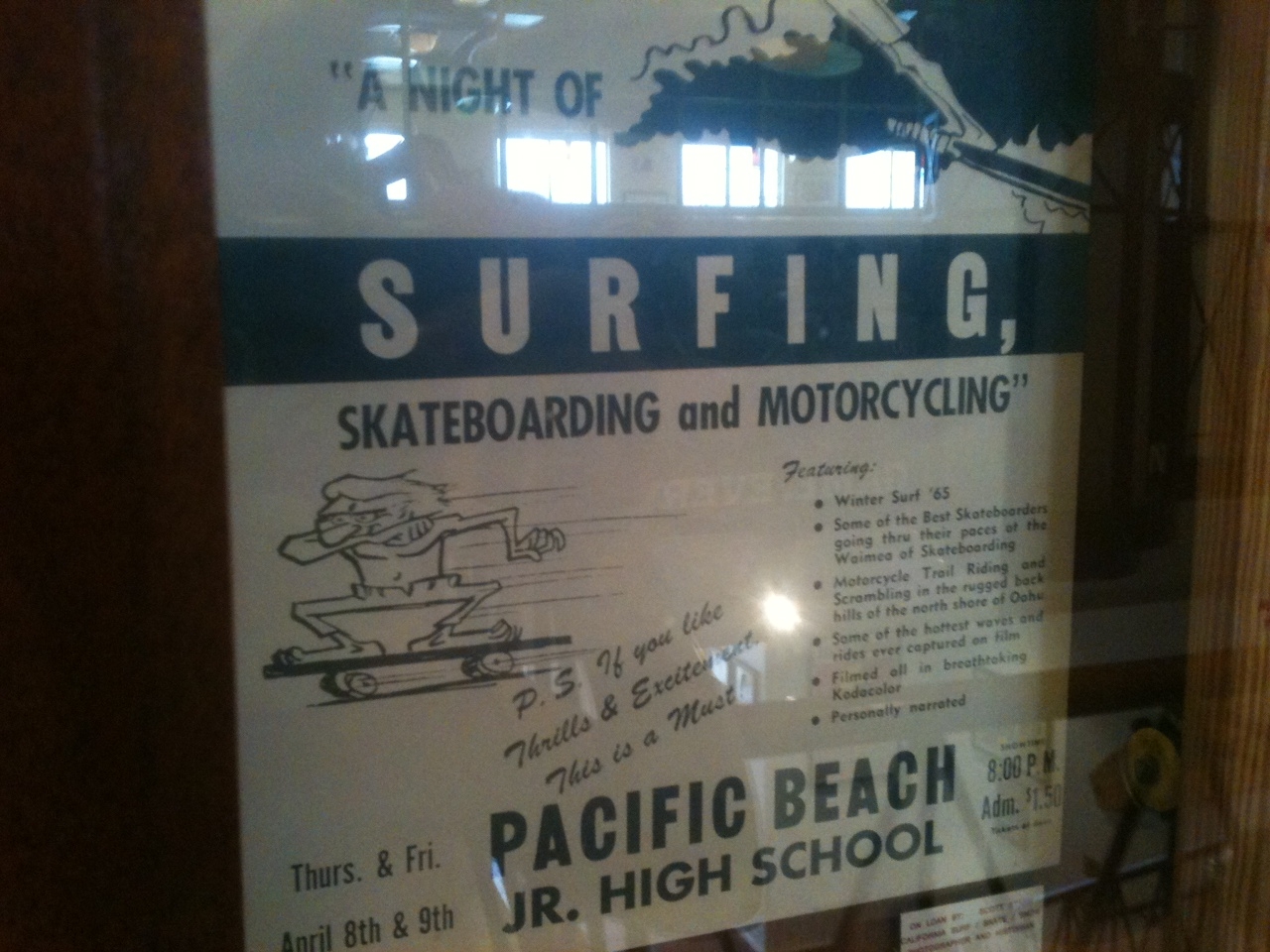

Photo Album – Surf

Discovering a New Species of Seabird in the Pacific

Peter Bryan Pyle

I had thought my best chance of discovering a new species of bird came and went during the late 1970s and early 1980s, when I worked on the Hawaii Forest Bird Survey. During this survey we slogged our way to very remote cloud forests that had never been adequately surveyed for birds. Less than a decade previous a surprising and distinct new species had been found on Maui, the Po’ouli, and our coverage of the tract where the Po’ouli was found, along with many similar unexplored tracts throughout Hawaii, was far more thorough than had ever occurred. During the survey we found some surprising new range extensions and a few species thought perhaps to be gone (and which probably are gone now) but, alas, no new species, despite intense due diligence. It appeared that the last frontiers for discovering new bird species were the very remote forests of South America and Southeast Asia, with discovery involving large and time-consuming expeditions. My career was taking me in other directions so it seemed I had lost my opportunity to discover a new bird.

One direction I took was the study of bird molt, and this required hours and hours of focused work in museum collections, examining 10’s of 1000’s of bird specimens. Most would consider this very tedious work, but I reveled in the discovery of any new tidbit about molt not previously known. The audience that shares my enthusiasm for these tidbits is next to non-existent, however, not quite the same as that enthused by a new species or, even, rumored rediscovery of one that was thought extinct (see Ivory-billed Woodpecker). Like pelagic trips to observe birds at sea, some days in the collections are better than others, and I was lucky to have a good day in August 2004 at the U.S. National Museum (USNM) in Washington, D.C.

Steve Howell and I were there for a week catching up on numerous projects of interest, including molt in water birds such as gulls and alcids and, for me, examination of some specimens that had been collected in Hawaii. I was helping my father with a monograph on the birds of the Hawaiian Islands, now on line, and one of my goals was to try to identify the subspecies of all migrant birds that had been recorded in the islands.

In February 1963 a small shearwater was collected on Midway Atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, identified as a Little Shearwater, given USNM specimen # 492974, and put in a dark drawer where it was left alone for over 40 years. There are five subspecies of Little Shearwaters that breed in cold regions of the south Pacific, and although the Midway specimen had, in 1968, been tentatively identified as the nominate (first described) subspecies from Norfolk Island, I wanted to confirm this against subsequent published information and to take some digital images of it for the monograph. But after a moment or two comparing it with other specimens of Little Shearwater at the museum, I was convinced that it was not the nominate subspecies of Little Shearwater and in fact was not even a Little Shearwater. But what was it?

Some of the specimen’s features were more like Audubon’s than Little Shearwater but it was too small for any of the Audubon’s Shearwater subspecies, and in fact appeared to be smaller than any other shearwater species. The closest contender was Boyd’s Shearwater, which breeds in the Azore Islands of the north Atlantic and also has characteristics in between Little and Audubon’s, so much so that ornithologists had considered a subspecies of each about half the time. The specimen did not quite fit Boyd’s either, however, and it would be very unusual to have a north Atlantic species occur on Midway. I suspected then that it might be an un-described subspecies or species, but knew that it would take more than just measurements and photographs of it to confirm this.

I ran all of this by Steve and USNM researcher Storrs Olson, who was studying small shearwaters including Boyd’s at the time, and Storrs suggested I examine its DNA to see if this could help place it. Thanks to Rob Fleischer and Andreanna Welch we eventually were able to compare DNA from the specimen with that of most other small shearwaters and indeed it proved to be more closely related to Newell’s Shearwater of Hawaii than Little or Boyd’s shearwaters and therefore was, in fact, a new species of bird. So I ended up getting my new species “the easy way” as those slogging the forests of South America might say, to which I respond that they should try spending 1000’s of hours in museum collections and see how easy it really is!

I got the opportunity to name the new species after my grandfather, Edwin Horace Bryan, and so it becomes “Bryan’s Sheawater (Puffinus bryani).” The big questions now are where does it breed and how can we conserve it? Another Bryan’s Shearwater was found calling in a rock crevice on Sand Island, Midway Atoll, in December 1991 and tape recorded. These Bryan’s Shearwaters may have been “prospectors” to Midway from other colonies, like the individual Short-tailed Albatrosses that visit Midway from colonies off Japan. It is also possible that Bryan’s Shearwaters bred undetected on Midway before rats were introduced there during World War II. Based on the timing of the records the species appears to breed in winter, and bird surveys there prior to the war were concentrated during spring and summer, so it could have been missed. Through the use of play-back recordings and decoys the U.S. Fish and Wildlife coaxed a pair of prospecting Short-tailed Albatrosses to nest and successfully fledge a chick on Midway for the first time during 2010-2011. And so the search now is on, to find where Bryan’s Shearwaters breed and, perhaps, to use recording of the 1991 bird to coax some back to Midway, to start a new colony now that the rats have been removed.

Photo Album – Vintage

California’s Shore Whaling Stations – Excerpts from the National Archives

History of the Shore Whaling Station

Shore whaling in California began at Monterey Bay around 1851, and proved to be so profitable that soon after whaling stations were established all along the Californian coast. During the second half of the 19th century whaling stations were established at Crescent City, Bolinas Bay, Halfmoon Bay, Pigeon Point (known then as Whale Point), Santa Cruz, Monterey Bay, Carmel Bay, San Simeon, Port San Luis (known then as Port Harford), Point Conception, Portuguese Bend, Dead Man’s Island and San Diego Bay. Although conventional ship whaling continued off the California coast at the same time as shore whaling, there was little competition.

Whaling ships confined their operations to the easier and more valuable right and sperm whales, while the shore whalers caught mostly gray and humpback whales. Industry and households depended on whale products for which there was no substitute. Whale oil was used for lighting and lubrication until 1860 when kerosene and petroleum started to gain popularity. The pure clean oil from sperm whales was a superior source of lighting and the finest candles were made from the whale’s wax-like spermaceti. Light and flexible, baleen – the bristle-fringed plates found in the jaws of baleen whales – had many uses in objects which today would be made out of plastic. No part of the whale was wasted in the modern whaling process.

Teams of flensers started from the head and stripped the blubber and then hacked it into manageable blocks. Pressurised steam digesters separated the oil from the liquid product which was dried, ground into powder and sold as whale meal for animal feed. In the 19th century, great iron cauldrons called trypots were used at sea and on shore for the stinking, greasy job of boiling down whale blubber. Pairs of trypots surrounded by bricks were called the tryworks. The blubber was heated and stirred until the precious oil separated out. It was then ladled into large copper coolers and later poured into casks for storage and shipment.

Whaling stations existed at the following points on the California coast. Others were on the Lower California coast, most of which, if not all, marketed their products in San Francisco: Crescent City, Bolinas Bay, Halfmoon Bay, Pigeon Point, Santa Cruz, Monterey Bay (2. stations), Carmel Bay, Point Sur, San Simeon, Port Harford (or San Luis Obispo), Cojo Viego (Point Conception), Goleta, Portuguese Bend (San Pedro), Dead Man’s Island (San Pedro), San Diego Bay (2 stations).

Mr. C. H. Townsend wrote in 1886 (Bull. United States Fish Commission): “of the eleven whaling stations mentioned by Scammon as established along the coast ten or twelve years ago, only five remain; those at Monterey, San Simeon, San Luis Obispo, Point Conception, and San Diego.”

There is considerable discrepancy as to when the different stations were started and abandoned, arising no doubt from loose organization. A station might be abandoned and so reported, but might start again either as the same company or another, or possibly a few fishermen with scarcely any organization would get together to try their fortunes at whaling. Some of the companies were composed of men who were fishermen or farmers a part of the year and whalemen the rest. Some organization, however, was necessary, for the property of a whaling company amounted to a thousand dollars or so, and shares had to be arranged.

The dates given must not be too seriously relied upon. Many of them were obtained from old men who based their recollections on relative incidents and personal experiences. For instance, at Pescadero the oldest inhabitants agreed on the years from 1862 to 1865 as the time of the beginning of whaling at Pigeon Point, until one old gentleman recalled very positively, and related in highly embellished English, how he had sold a yoke of oxen to Captain Bennett in 1865 “and the station had at that time been running exactly three years.”

Bolinas Bay Station

This was not included in the list of stations of either Scammon or Goode, though in some respects it was more important than any other. Probably the industry did not warrant such an ambitious scale as this company operated on and it did not last long. The company, according to the Daily Alta California, San Francisco, November 13, 1857, was capitalized at $100,000, and was known as the Bolinas Bomb-lance Whaling Association. It had a commodious dock and try works, and a steam engine for hoisting and oil refining purposes. In some respects the operations of this company resembled those of the more modern whaling stations than they did those of the stations of its own time. It had a fleet of small vessels that cruised about taking whales and flensing them alongside the ships. About biweekly the ships would land their cargo of blubber at the dock, where the oil was tryed out and refined. The account stated that the company contemplated the purchase of a steamer to tow their vessels over the bar.

Japan Tsunami hits the Central California Coast

Below is a report written the morning after Japan suffered a 9.0 earthquake in March of 2011, and on the day the tsunami waves hit California. Please also find below an intriguing article explaining the effect on the earth’s tectonic plates and the earth’s axis from this enormous earthquake.

There’s a Reason Tsunami is a Japanese Word

I happened to catch the live reports from Japan last night just after the massive earthquake hit and the tsunami’s began rolling in.. No sleep for me. On my mind were friends and family on Midway and in Hawaii, and most of all I couldn’t shake the surreal visions of tsunami waves and devastation in Japan. Our hearts and thoughts are with Japan tonight.

So – it was up early for me, check-in with Hawaii, then hit the road for semi high ground at the Marin coast. The sea change was subtle at first, but by 9:00 a.m., March 11, 2011 had become the eeriest day of my life. In an instant the good-sized surf fell quiet and calm, and the ocean’s retreat revealed so much rock and sea floor further and further out that it sent shivers up my spine, and exclamations from the onlookers around me. The ncoming surge and swells that followed soon churned and rumbled-in, flooding Stinson Beach, Bolinas Beach and the Bolinas Lagoon completely. This pattern continued for every half hour until I left the scene at noon.

Cormorants sat confused on the beach, and at one point a large Leopard shark was swept in and dumped on the retreating sands of the beach below, thrashing and rolling until a surge brought relief to the fish about 20 minutes later. We later heard that mild surges were clearly detectable up and down the coast of California through the night of the 11th, and into the next day – for at least a 24 hour period!

Reports of harbor and shoreline damage up and down the California coast keeps trickling- in from locations such as Crescent City, Fort Bragg/Noyo Harbor, Berkeley Marina, Santa Cruz Harbor, Morro Bay, and Catalina Harbor. We have MUCH to learn regarding the science of tsunamis, and much to learn from Japan’s unparalleled preparedness and response to earthquakes.

Japan’s earthquake shifted balance of the planet – Liz Goodwin – Mon Mar 14, 2011

Last week’s devastating earthquake and tsunami in Japan has actually moved the island closer to the United States and shifted the planet’s axis.

The quake caused a rift 15 miles below the sea floor that stretched 186 miles long and 93 miles wide, according to the AP. The areas closest to the epicenter of the quake jumped a full 13 feet closer to the United States, geophysicist Ross Stein at the United States Geological Survey told The New York Times.

The world’s fifth-largest, 8.8 magnitude quake was caused when the Pacific tectonic plate dove under the North American plate, which shifted Eastern Japan towards North America by about 13 feet (see NASA’s before and after photos at right). The quake also shifted the earth’s axis by 6.5 inches, shortened the day by 1.6 microseconds, and sank Japan downward by about two feet. As Japan’s eastern coastline sunk, the tsunami’s waves rolled in.

Why did the quake shorten the day? The earth’s mass shifted towards the center, spurring the planet to spin a bit faster. Last year’s massive 8.8 magnitude earthquake in Chile also shortened the day, but by an even smaller fraction of a second. The 2004 Sumatra quake knocked a whopping 6.8 micro-seconds off the day.

After the country’s 1995 earthquake, Japan placed high-tech sensors around the country to observe even the slightest movements, which is why scientists are able to calculate the quake’s impact down to the inch. “This is overwhelmingly the best-recorded great earthquake ever,” Lucy Jones, chief scientist for the Multi-Hazards project at the U.S. Geological Survey, told the Los Angeles Times.

The tsunami’s waves necessitated life-saving evacuations as far away as Chile. Fisherman off the coast of Mexico reported a banner fishing day Friday, and speculated that the tsunami knocked sealife in their direction.

Photo Album – North Coast Journey

A Conversation with Peter Banks – California Archeologist